United to End Polio

From Pakistan, to the Netherlands, to Chad

Our World United to End Polio profiles individuals from around the globe who have committed their expertise, time and passion to the global effort to eradicate polio. It's a journey that began in the Americas in the 1980s, has crossed every continent, and is now focussed on a handful of countries still facing polio outbreaks.

In this series, engage with an immersive multimedia experience: photos, videos, animation and stories about people who have given everything to end a disease.

Meet Naureen, a community-based vaccinator dedicating her time to protecting families in high-risk areas of Karachi.

Naureen

Naureen

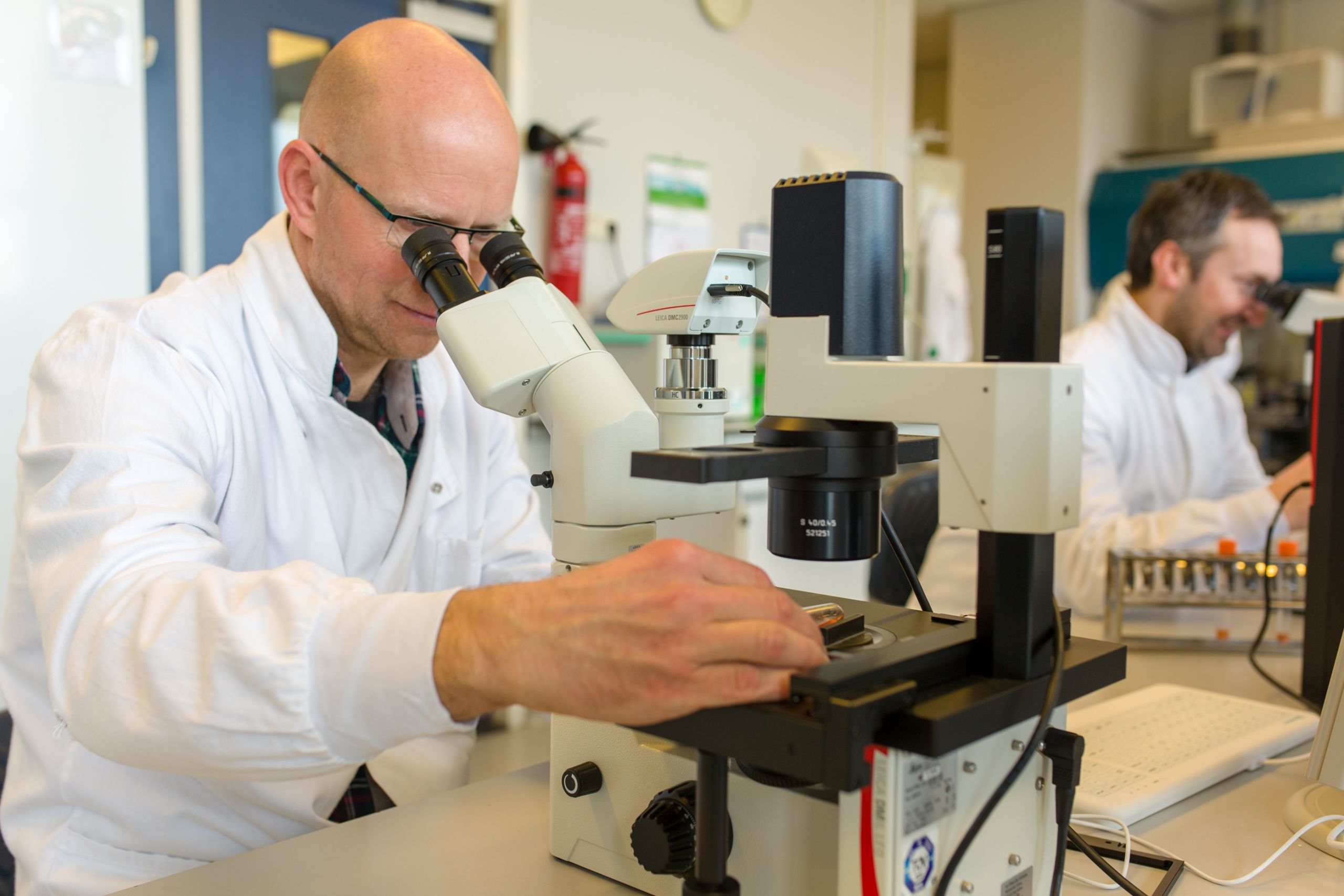

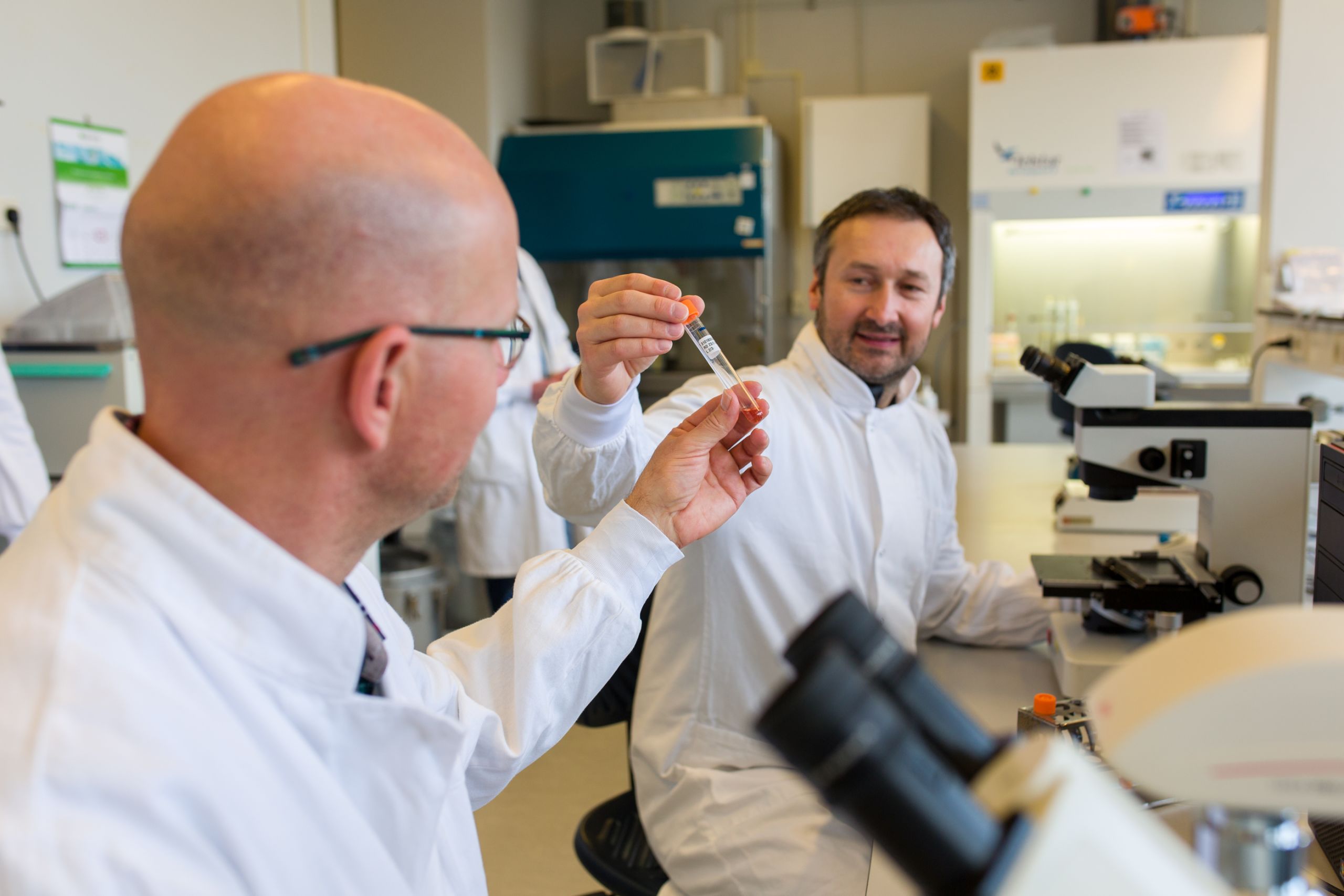

Dr. Erwin Duizer is a polio laboratory specialist working on the cutting-edge of laboratory safety.

Dr. Erwin Duizer

Dr. Erwin Duizer

Dr. Adèle Aluma, from the Democratic Republic of Congo, has travelled to areas on Lake Chad few health workers have been.

Dr. Adèle Aluma

Dr. Adèle Aluma

And meet Awandi Epainette, a nurse working to reach nomadic communities, as they move around the Lake Chad Basin.

Nurse Awandi Epainette

Nurse Awandi Epainette

To experience these stories, simply scroll down.

To engage with a new story, click a headline on the menu bar.

Community-Based Vaccinators

Reaching every home

in high-risk areas of Pakistan

It’s 7 am and the sun is baking the rooftops and roads of Kemari, a dusty suburb of Karachi. About 30 women, most in niqab, gather on a small rooftop and listen to instruction about the day’s work. It’s going to be hot and difficult, as the women prepare to visit dozens of households before the day is done. They are community-based vaccinators.

“Every team must check if their marker is working,” says the supervisor. “Ask yourself, is your vaccine carrier ok? Is the vaccine in good condition?”

Fifteen minutes later and the women are making their way downstairs to gather the polio vaccines and vitamin A capsules. They place them in carriers shaped like thermoses.

Outside, the neighbourhood is lively. People from all over Pakistan and Afghanistan live here. Children hold hands on their way to school. Groups of men cluster around shops where bakers turn fresh parathas on a giant skillet. Women are mostly absent.

Suddenly a man steps into the health offices. He gestures. He shouts. He doesn’t want his children to be vaccinated. He says the vaccine is dangerous and made his kids sick. If he unnerves the women, they don’t show it. Two security officers talk to the man. He backs away for a moment and then charges forward again. He won’t stop shouting.

The community vaccinators slide past him to begin their work.

Naureen is a community-based vaccinator on the team. To learn more about her work, you can watch this video, or, scroll down to read more.

Learn how Naureen does her work in a high-risk area of Karachi.

Learn how Naureen does her work in a high-risk area of Karachi.

Polio in Pakistan: A Fraught History

Pakistan has been trying to eradicate polio for three decades. It's been tough, especially since 2001. Increased migration from Afghanistan, which is also polio-endemic. Insurgencies. Inaccessible areas under militant control. A health system that struggled to reach the poorest people. A large birth cohort. A catastrophic earthquake. Flooding. Lack of political will. A decentralisation of the health system, leaving no one with central control over the polio eradication programme.

Polio cases declined one year, only to rise again the next. Communities grappled with rumours: “The vaccine will sterilise your child.” “The vaccinators are spies.” “The vaccine contains alcohol.”

In 2011, the program received an overhaul. There were committees formed at each administrative level, and more accountability up and down the chain of command. Polio campaign performance improved. The Prime Minister expressed support.

Then, women vaccinators started to be murdered. In December 2012 in what appeared to be a coordinated attack, five women were killed while working on the polio campaign in Karachi. Three of the victims were teenagers. They were the first of more than nine murdered that month. Murders continued through 2013 and 2014. Women, drivers, security personnel. By the end of 2015 almost eighty people had been killed.

Polio case numbers tracked closely to insecurity. Where there was little access, there was polio.

In 2013 there were 93 cases of polio in Pakistan. In 2014 – the worst year for the program - there were 306. That year, the World Health Organization called Pakistan’s polio situation a public health emergency of international concern.

In the report from its October 2014 meeting, the International Monitoring Board for polio called the Pakistan polio program “a disaster” and called Pakistan a “major stumbling block to global polio eradication.”

2016 : A turning point

In 2016 the situation improved. Over the previous two years, Pakistani forces had retaken areas once under militant control. As security and access improved, some communities continued to harbour mistrust, and refused to have their children vaccinated.

Often, vaccinators were men who, under cultural norms, could not access homes if the man of the house was not present. Or, they were strangers to the community.

A 2017 Harvard survey reinforced the fact that communities needed not only to trust the vaccinators, but that they preferred women to be represented. Of those polled, 82% said they preferred women in the teams.

Pakistani polio leaders identified areas that were at high-risk for polio. Areas with many refusals, or high rates of migration.

Managers began hiring local people – mostly women - to be vaccinators in their own communities. They were assigned a number of houses for which they were responsible. Their jobs were to register families and understand their basic health status – whether women were pregnant, how many children were in the household and how many of those had been fully vaccinated. Instead of vaccinating every few weeks, the women visited regularly to check in with the household and inform them of services such as routine vaccination clinics.

These vaccinators had different titles in different areas, but have come to be known as community-based vaccinators, or CBVs. Naureen is one of them.

Naureen has been working as a CBV for about a year. She is amongst the women who gather on the rooftop in Kemari in the morning to make their plans and receive their allocations of vaccine and other supplies.

She is one of the woman who remained unruffled by the man shouting about the polio vaccine.

“I know everyone in this community and I have no problems."

In the morning, she and her supervisor, Iffat, walk down the narrow alleyways towards the homes for which they are responsible (Naureen has 92). At one curtained door Naureen calls out to the head of household. She has a quick word with the mother of the house to let her know a photographer is present. The adult women in the compound are welcoming. They say they don’t want to be photographed but they’re happy for Naureen to be photographed vaccinating their children.

Naureen marks the finger of a young girl to show she's been vaccinated against polio.

Naureen marks the finger of a young girl to show she's been vaccinated against polio.

Naureen spots a newborn sleeping in a hammock and kneels down beside her. She unzips her vaccine carrier and pulls out a vial with one hand while waking the baby with the other. Within seconds Naureen has dropped the polio vaccine into the baby’s mouth. The baby puckers her lips, clenches her eyes and is soon back asleep.

Naureen wakes this baby for just a few seconds to give her polio vaccine.

Naureen wakes this baby for just a few seconds to give her polio vaccine.

Naureen says the work is not always this easy. Her area is considered “high-risk” with movements of families coming from Afghanistan and the conflict-affected Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Nearby, environmental samples have tested positive for poliovirus. In a previous campaign round more than 100 children had not been vaccinated due to parental refusal.

“There are many types of groups in this community,” says Naureen. “We hear good and bad comments, but most people are cooperative and usually understand and comply.”

When families refuse Naureen says she is patient, and spends extra time explaining the safety and value of the vaccine.

“This vaccine can be questionable to people at times. Some think it’s like contraceptives and will hurt the community. I explain that this vaccine is like building a house and putting a roof on top of it. The roof protects you from the rain and the sun.”

Naureen's supervisor, Iffat, after she and Naureen vaccinated all children in the household.

Naureen's supervisor, Iffat, after she and Naureen vaccinated all children in the household.

Naureen moved to Karachi from Peshawar 17 years ago, when her husband lost his business and the family’s income. She's now 44. Her family ensured she got a high school education, and that’s the reason she can work as a community-based vaccinator today.

Naureen makes tea for some friends.

Naureen makes tea for some friends.

Polio managers recognize Naureen’s contribution together with that of all the CBVs. Whereas the polio Independent Monitoring Board called Pakistan’s program “a disaster” in 2014, one year later it praised the hiring of local female vaccinators and suggested the model be scaled-up.

It was. By 2017 the total CBV workforce was almost 18,500 people, the majority of them women. They were reaching more than 3.7 million children every polio campaign.

The Polio Emergency Plan for 2017-2018 notes that “The local, female profile of the vaccinator remains the cornerstone in building trust with caregivers and the community… In the core reservoir districts, the implementation of the CBV approach has been a boon for the programme.”

The results are clear. In 2017 there were just eight cases of polio in Pakistan. As of September 2018, there are four.

Naureen remains motivated. “We really like the fact that we have almost ended polio. It’s exciting that we are beating this disease in Pakistan."

"My mission is to end polio, and then help stop other childhood diseases.”

A Poliovirus Spill

Lessons for Containment

Accidents happen despite the best precautions. In vaccine manufacturing, there may be an incident or two every year where the operators risk contamination.

When these incidents occur, manufacturers and public health authorities follow strict safety procedures, and operators are tested for infection.

“In the eight years I’ve been here, we’ve had notifications of several incidents, and the results were always negative,” says Dr. Erwin Duizer, the head of the Netherlands’ National Polio Laboratory at the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (commonly referred to as RIVM).

Bilthoven Biologicals, where the poliovirus spill took place last April 2017.

Bilthoven Biologicals, where the poliovirus spill took place last April 2017.

On April 3, 2017, there was a poliovirus spill at Bilthoven Biologicals - a manufacturer that is located next to Duizer’s workplace.

Watch the video below to see how Duizer and his colleagues managed the spill, and continue scrolling to read more.

Dr. Erwin Duizer describes the impact of a poliovirus spill at a vaccine manufacturer.

Dr. Erwin Duizer describes the impact of a poliovirus spill at a vaccine manufacturer.

The company was producing inactivated polio vaccine – an injected vaccine that contains a killed poliovirus. As part of the process, live virus is released from one large pressurized container through a tube, to a separate container where the virus is subsequently inactivated.

Somewhere along that route, a valve was not operating properly, and nearly a litre of liquid containing live virus splashed to the floor. Due to the pressure, some liquid also aerosolized, putting both operators at risk of poliovirus infection.

In the manufacturing process, live virus moves through high-pressure pipes.

In the manufacturing process, live virus moves through high-pressure pipes.

“When these incidents occur, our protocol is to obtain stool and throat samples, and test operators for infection,” says Duizer. “We take every incident seriously, and as this was a type 2 wild polio virus incident, we were even more attuned to its importance.”

Live virus leaked from the pipe due to a faulty valve, and aerosolised around the operators.

Live virus leaked from the pipe due to a faulty valve, and aerosolised around the operators.

Wild type 2 poliovirus was declared eradicated in 2015 and hadn’t been found outside a laboratory since 1999, when it was last identified in northern India. Duizer knew that a worker shedding type 2 polio in public was counter to global poliovirus containment protocols – known as the “GAP III” – an essential strategy towards eventual certification of global polio eradication.

There was one major issue with the testing. Poliovirus normally begins to shed in the stool four days following potential infection. Therefore, the Dutch protocol at the time was to test the operators’ samples on the fourth day.

A Friday Test

It was late on a Friday afternoon. Duizer and his colleagues examined the initial test results, and they showed positive for type 2 polio virus. “I said to the technician, ‘this is type 2, and this has some consequences if this is really positive. Please repeat the test.’ So, on Friday at 5 pm he began re-doing everything and it took about five hours.”

The result was again positive for type 2 wild poliovirus.

Duizer set the next protocol in motion and called the polio response team.

The operator had of course been vaccinated, but he was shedding type 2 poliovirus.

In the four days before he was tested, he had been living at home with his family, using the home bathroom, and traveling back and forth to work on public transport.

“The risk to the public was small as the Dutch sewage system is closed, and the majority of people are vaccinated,” explains Dr. Duizer.

“But there are groups of unvaccinated people living in the Dutch Bible Belt, where vaccination rates in communities are often below 90 percent and at some schools it can be as low as twenty percent.” The operator, it turned out, hadn’t travelled to those areas.

Once the operator was confirmed positive for poliovirus, he had to go into isolation, use a toilet that wasn’t connected to the sewage system, and his family had to be tested routinely for polio.

“They were very cooperative, though I imagine it wasn’t much fun for them,” says Duizer.

The operator remained in isolation for 29 days following the initial contamination. There were no further infections.

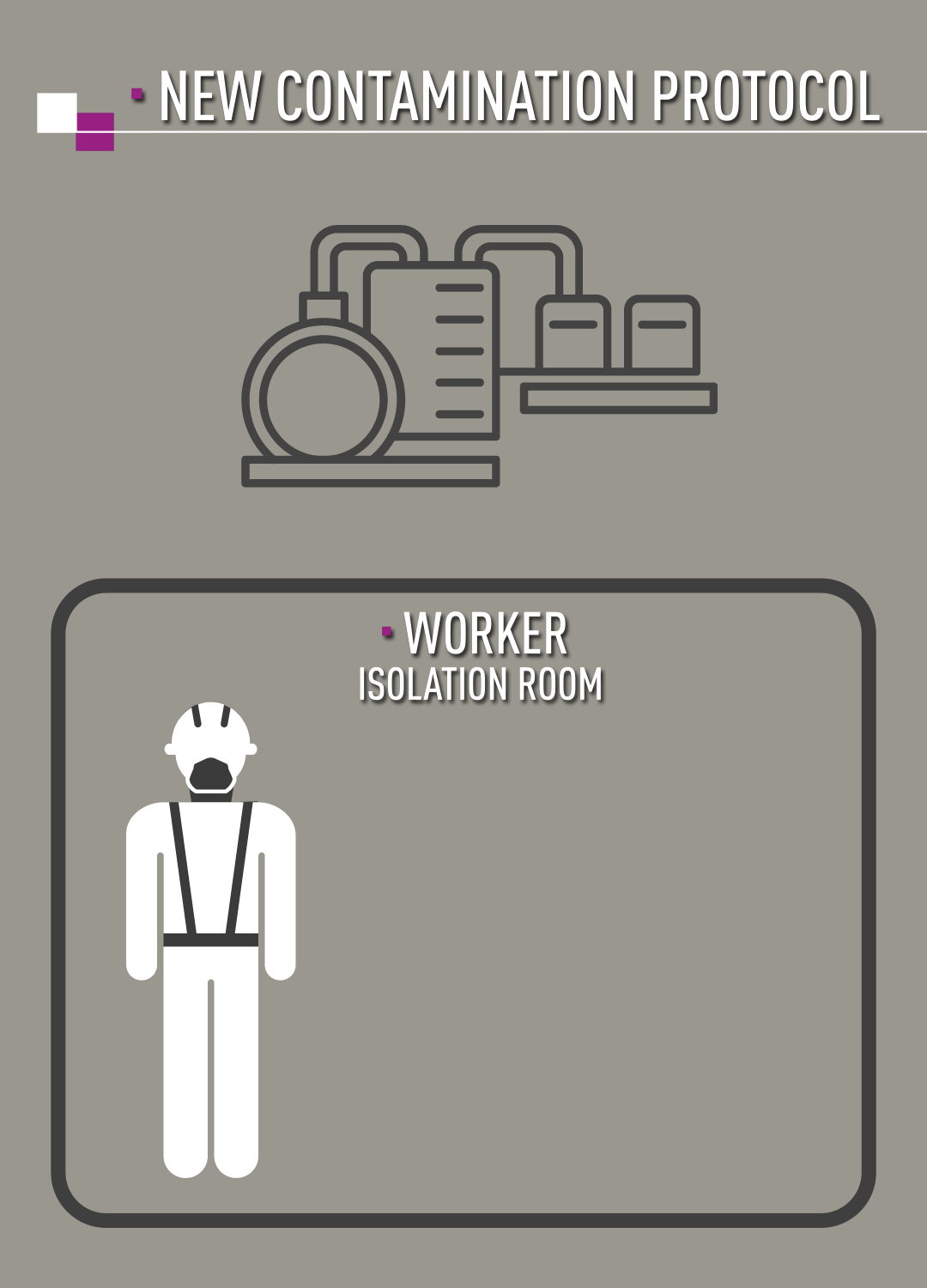

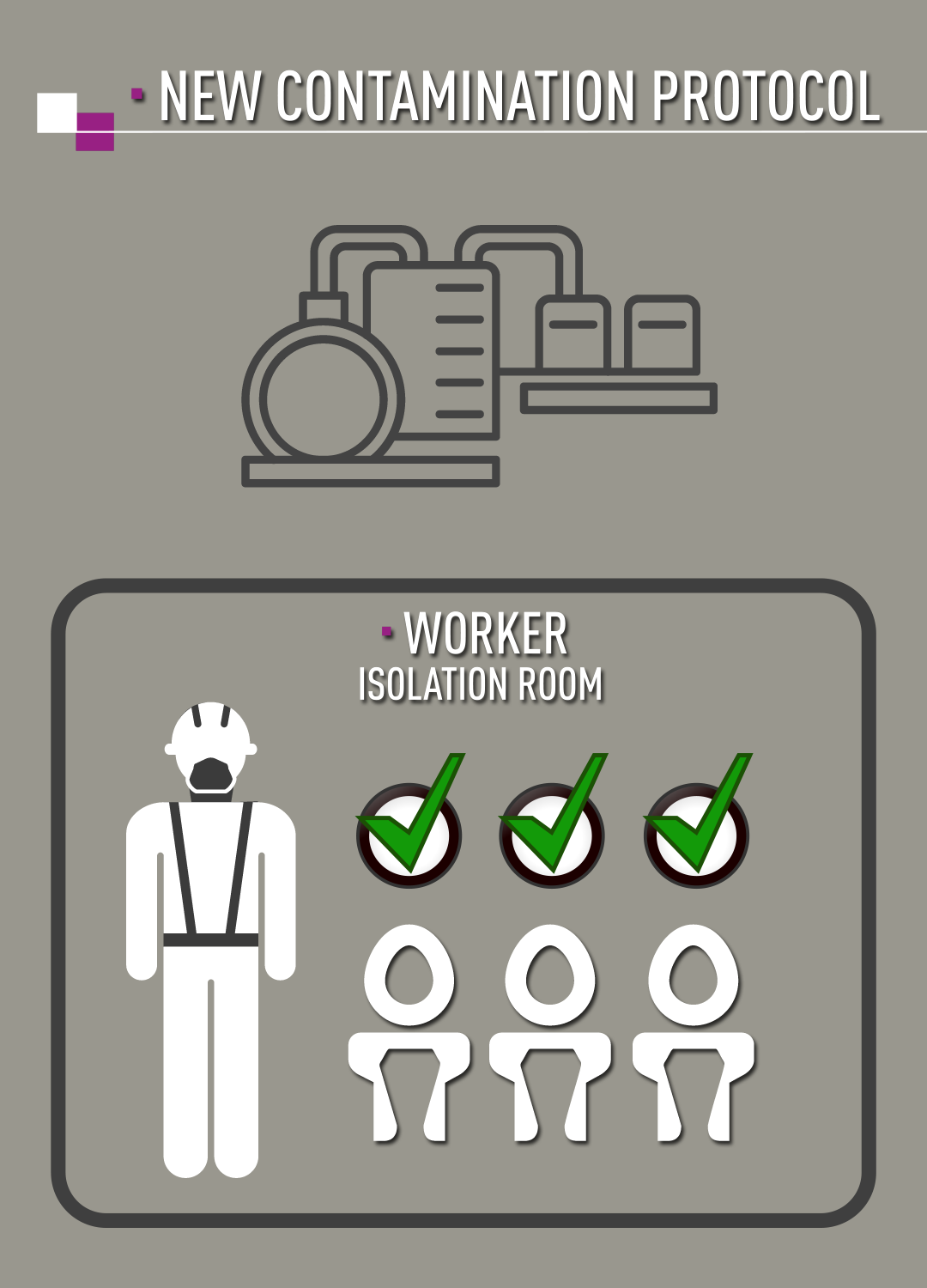

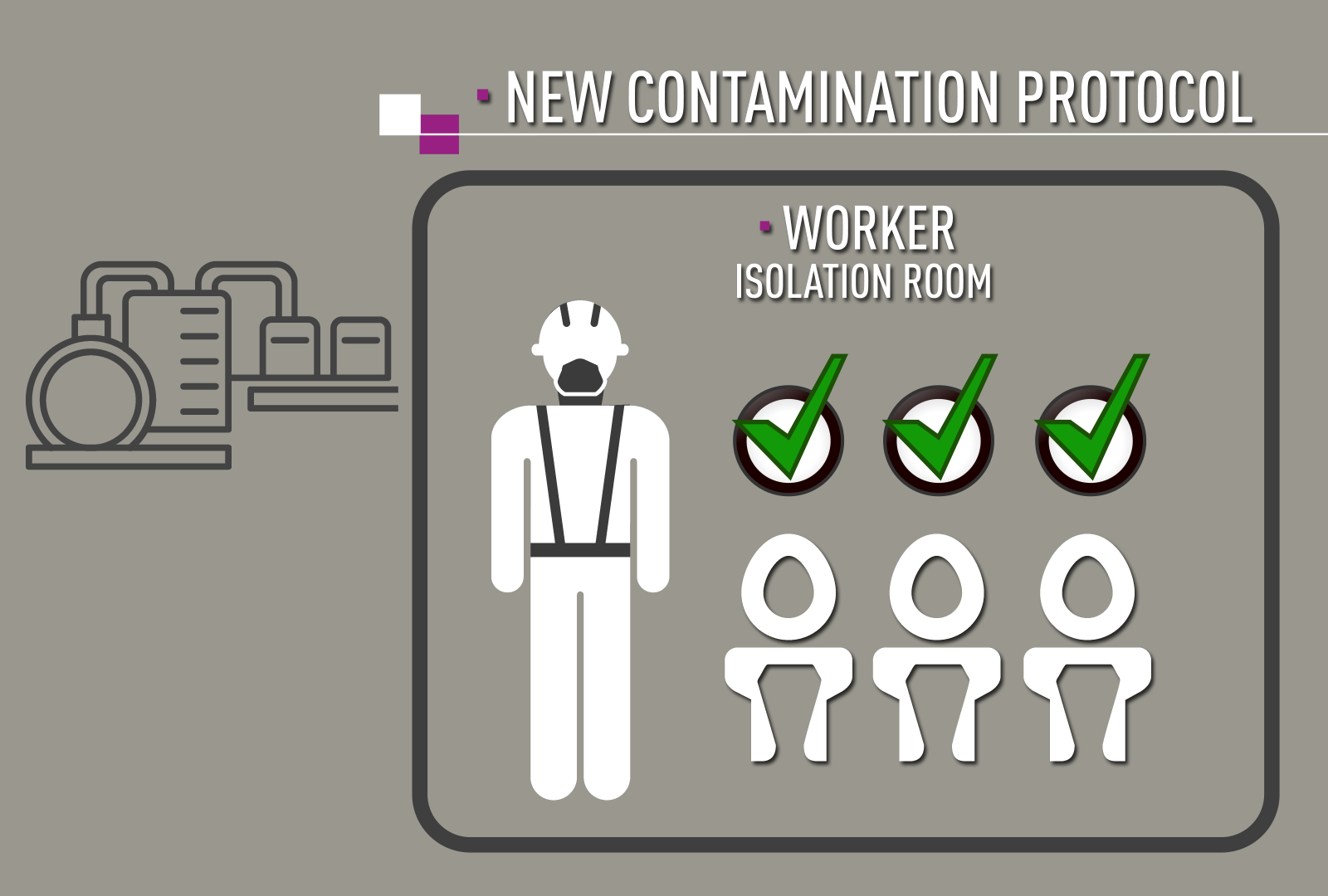

New Protocols

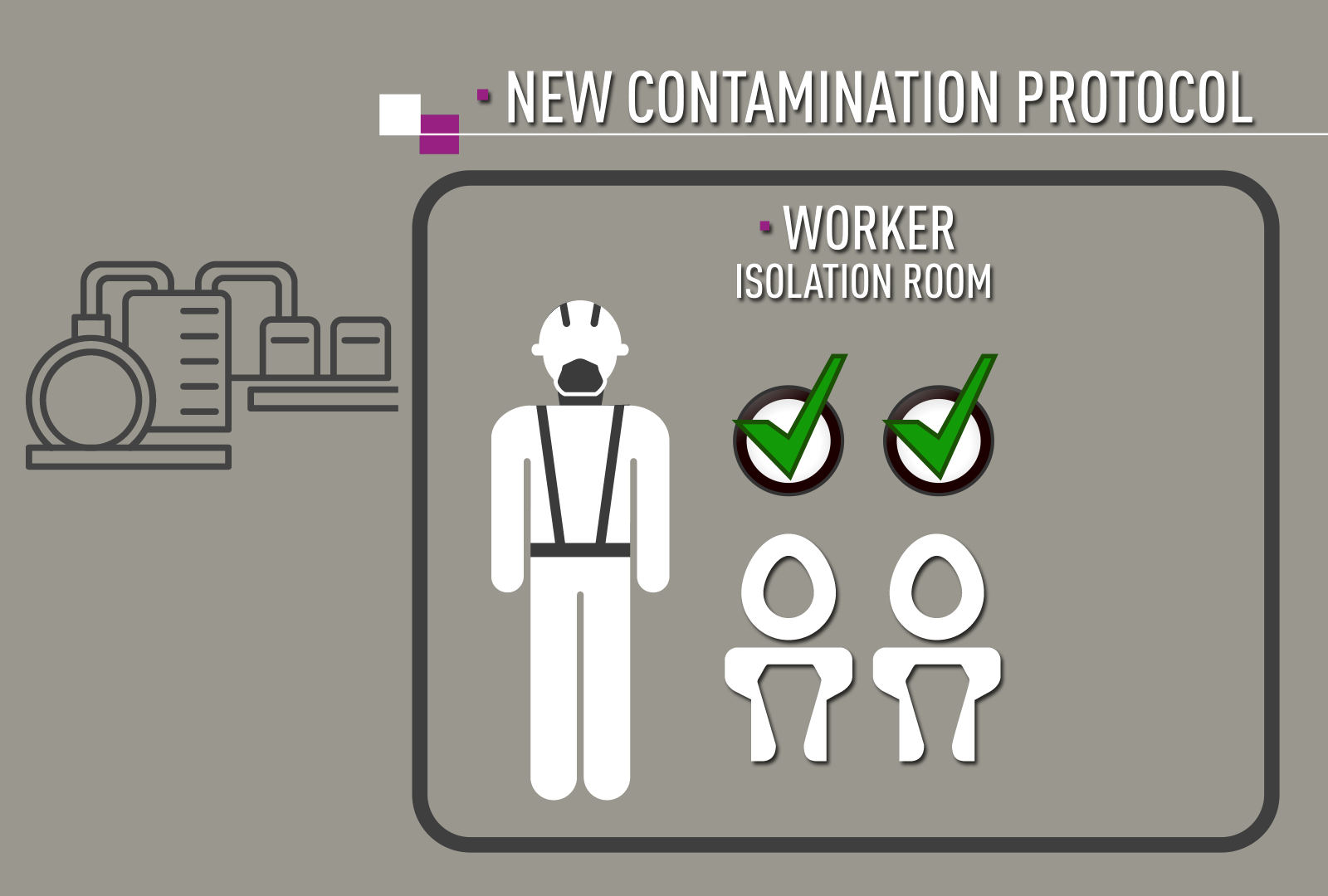

Duizer says the incident taught some immediate lessons, and as a result, he and his colleagues have been updating the Dutch protocols.

“As a first step, any operator who may have been contaminated goes immediately into isolation in an apartment.”

Under the new protocols, the operator would go into isolation right away.

“Next, stool will be tested from day one and not day four as before.” The operator would use a dry toilet that is not linked to the sewage system. “Only after three days of negative test results can the worker be taken out of isolation,” says Duizer.

Only after three days of negative test results can the worker be taken out of isolation.

In preparation for future incidents, the Dutch National Polio Laboratory has acquired containment kits including dry toilets and other supplies such as gloves, sample kits and chlorine tablets.

“As countries work to implement poliovirus containment as outlined in GAP III, these incidents offer real-life opportunities to learn and refine our protocols,” says Dr. Duizer.

“When to test? When is isolation necessary? For how long? How to handle the ethics of potential isolation for family members or contacts? We now have practical answers to these questions.”

“We would have preferred for this type 2 poliovirus incident not to have happened,” says Duizer. “But we know realistically that accidents will happen. The key is to identify, and report incidents quickly, and then act using clear protocols. "

"We’ve learned a lot, and we’re ready for future incidents.”

Under the new protocols, the operator would go into isolation right away.

Under the new protocols, the operator would go into isolation right away.

Next, stool will be tested from day one. The operator would use a dry toilet that is not linked to the sewage system.

Under the new protocols, the operator would go into isolation right away.

Next, stool will be tested from day one. The operator would use a dry toilet that is not linked to the sewage system.

Only after three days of negative test results can the worker be taken out of isolation.

Only after three days of negative test results can the worker be taken out of isolation.

Only after three days of negative test results can the worker be taken out of isolation.

Across the Sands

Reaching the Children of Chad

A man with a yellow vest calls through a megaphone, seemingly to no one. "Come for vaccination!" In the near distance there are wooden structures built around the trunks of neem trees. This desert neighbourhood feels quiet.

But soon, women emerge, children in their arms, small ones in tow. They walk towards the man with the megaphone. He stands beside a group of health workers assembling a temporary vaccination post under a tree. The mothers and children gather and sit on mats and blankets. Older boys and men do the same.

A group of women and children approach the health post.

A group of women and children approach the health post.

“When the people can’t come to the health posts, we need to go to the people,” says Abdel Aziz Kadai, a Chadian who works as a consultant for UNICEF.

Watch this video about the ways health workers in Chad are reaching nomadic and refugee children, or continue scrolling to read more.

See how polio teams are reaching nomadic communities and refugees with all vaccines.

See how polio teams are reaching nomadic communities and refugees with all vaccines.

Efforts to go directly to the people are the focus of the polio eradication work in the Lake Chad Basin area.

“We can’t eradicate polio without the communities,” explains Kadai. “It’s because of community support that we can reach vulnerable children. This includes island communities, nomads, refugees, the internally displaced and children at markets.”

Abdel Aziz Kadai, UNICEF Communication for Development Consultant

Abdel Aziz Kadai, UNICEF Communication for Development Consultant

The Polio Risk

Chad hadn’t recorded a case of wild polio virus since June 2012. However, when neighbouring Nigeria identified a case of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus in August 2016, it was genetically linked back to a virus circulating in Chad last seen in 2013. Clearly children were still being missed. From that moment, the polio program reinstated a polio emergency in the Lake Chad basin.

Lake Chad is at the intersection of four countries: Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria.

People trade across the borders. Nomadic communities move from place to place to graze their herds of cattle, sheep or camels. And in more recent years, the threat of Boko Haram, the militants who have terrorised communities in north-east Nigeria, has led to massive displacement. In 2015, people fled Nigeria for Chad, and within Chad, people left their island settlements to seek safety in the desert.

Given these shifting conditions, combined with an unforgiving geography of remote islands and endless desert, it's tough to reach every child. New babies are born every day. Surveillance for polio is not as strong as it needs to be.

Polio could be circulating, but the system may not know it’s there.

Therefore the Lake Chad Polio Task Team has two main goals: improve surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis, and raise polio immunity amongst the most vulnerable children. The Task Team coordinates a series of “special activities” aimed at vaccinating children under ten years of age who might otherwise be missed. Health workers bring routine immunization together with polio vaccine whenever they can.

The effort comes at a cost- about $6 million from June 2017 to June 2018. Another $2.3 million have been raised for additional campaigns for the next phase of the effort. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have been the main funders.

“The Lake Chad Basin polio activities must be sustained until Africa is certified polio-free,” stresses Dr. Sam Okiror, who coordinates the Task Team. “If we stop, we run the risk of another outbreak.”

Dr. Sam Okiror coordinates the Lake Chad Polio Task Team.

Dr. Sam Okiror coordinates the Lake Chad Polio Task Team.

Mafou Nomadic Community

Kadai, the UNICEF consultant, stands with nurse Awandi Epainette as he talks with the community, explaining why vaccination is important. He speaks in French and in turn, an interpreter translates into Kanembou, the local language.

Epainette asks the mothers to show their vaccination cards. One lady pulls a card from inside her clothing. It’s faded and torn, but she has it. She seems to be the only one. That’s not terribly surprising. Not so long ago, routine immunization coverage in this part of Chad was very low. According to UNICEF/WHO estimates, perhaps one in three children were vaccinated. Amongst nomadic communities, coverage was likely lower.

“The nomads are always on the move,” explains Nurse Epainette, in charge of the nearest health centre. “One day they are here in my health district and the next they may be many kilometres away.”

“We are trying to raise awareness,” says Dr. Aimé Matela, a consultant with the Lake Chad Polio Task Team. “We’ve identified community leaders who can coordinate with the health centres. They can determine when and where nomadic children can be immunized.”

Huge Community Demand

On this day, the community demand is clear. When the vaccinators ask children to stand in a line for polio vaccine, kids don’t hesitate. Mouths open, eyes shut, two drops. Within twenty minutes almost 100 kids have been vaccinated against polio.

The same holds for routine vaccination. Mothers wait while each baby under one year of age receives protection against diseases like hepatitis B, measles and meningitis A. Eligible women are vaccinated against tetanus, protecting them and their future newborns.

“The polio eradication campaigns help us so much with routine immunization,” stresses Nurse Epainette. “Before they were more difficult to combine. The polio consultants working for the Task Team have helped us to organize the routine sessions and this is working very well."

Nurse Epainette is fully satisfied with the session. “In this area everyone is on board with vaccination. The leader of the community can even name diseases that are prevented by vaccines. Everybody responds so well, and that makes me very happy.”

These continued efforts, he says, will put an end to polio.

“Health workers and our health liaisons, village leaders, all of us – we want to put polio behind us. We are giving everything to do that.”

Nurse Awandi Epainette.

Nurse Awandi Epainette.

Across the Waters

Reaching all children on Lake Chad

The boat moves with ease through the open waters of Lake Chad. Until it comes to a dead stop.

In an instant, the boat is surrounded by large floating clumps of heavy earth and grasses, that unpredictably shift and wedge between the dozens of island channels on the lake. The 20-foot wooden boat is now trapped in an unnavigable temporary land mass.

The chorus: “Maintenant il faut pousser!” “Now, we must push!”

Three men jump into the shallow water and they push with all their might. The sun is high. Sweat beads. Inside the boat, the captain, head wrapped in a white cotton scarf, reverses the engine. Several more men grab long oars and push to one side of the boat. The captain revs the engine forward. Then backwards again.

“Yallah yallah yallah!” “Go go go!” The men push and pull.

It takes twenty minutes or more. Finally, the boat is set into a narrow path through the heavy grasses.

For this entire episode, Dr. Adèle Daleke Lisi Aluma sits comfortably in the boat. She’s not worried. This is one of the easiest islands journeys she has taken.

Dr. Adèle Daleke Lisi Aluma and her colleagues from the Lake Chad polio team.

Dr. Adèle Daleke Lisi Aluma and her colleagues from the Lake Chad polio team.

Watch the video about Dr. Aluma's efforts to reach children on the hundreds of islands of Lake Chad, and scroll down to read more.

This video shows how health workers are reaching children on hard-to-reach islands on Lake Chad.

This video shows how health workers are reaching children on hard-to-reach islands on Lake Chad.

Communities at risk

As a consultant with the Lake Chad Polio Task Team based in the Bol district of Chad, part of Aluma's job was to raise polio vaccine coverage in an area where almost half the population live on islands. It’s an area where the risk of poliovirus circulation was high.

“I’ve visited several islands where no children had been reached with any vaccines for three or four years,” she says.

One reason children haven’t had services is the distance and difficulty of reaching the islands. “No one wanted to take the time and energy to go,” says Dr. Adèle.

Dr. Aluma says she’s travelled for up to twelve hours to reach just one of the distant island health centres. The journey is difficult: first by a larger boat with an outboard motor; then by pirogue, which are narrow and often leaky; then by foot, at times waist-deep in water; and by motorcycle on the islands when one is available.

“And when there’s no motorcycle, you walk some more,” says Aluma.

All of this transport takes time and costs money. Boatmen and motorcycle drivers must be paid for their time and the fuel. “Visiting all of the health centres in the Bol district alone required 800 litres of fuel,” says Aluma. “This is expensive to sustain.”

Another barrier is security. A few short years ago, Boko Haram militants from neighbouring Nigeria crossed onto some Lake Chad islands as they were chased away by the military. Communities fled the islands and had to leave everything behind.

Security sometimes need to accompany teams on Lake Chad .

Security sometimes need to accompany teams on Lake Chad .

“Fishermen lost their boats,” explains Aluma. “Herders lost their cattle, camels or sheep. Any health services that may have existed were completely interrupted.”

As Aluma supports local health workers to plan polio vaccination campaigns, she and her colleagues are aiming to at once raise coverage of polio vaccine and to improve the polio surveillance system.

They have identified new settlements through travel, and by using satellite mapping technology supported by the Lake Chad Polio Task Team in the capital, N’Djamena. That team is led by Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partnership Coordinator, Dr. Sam Okiror.

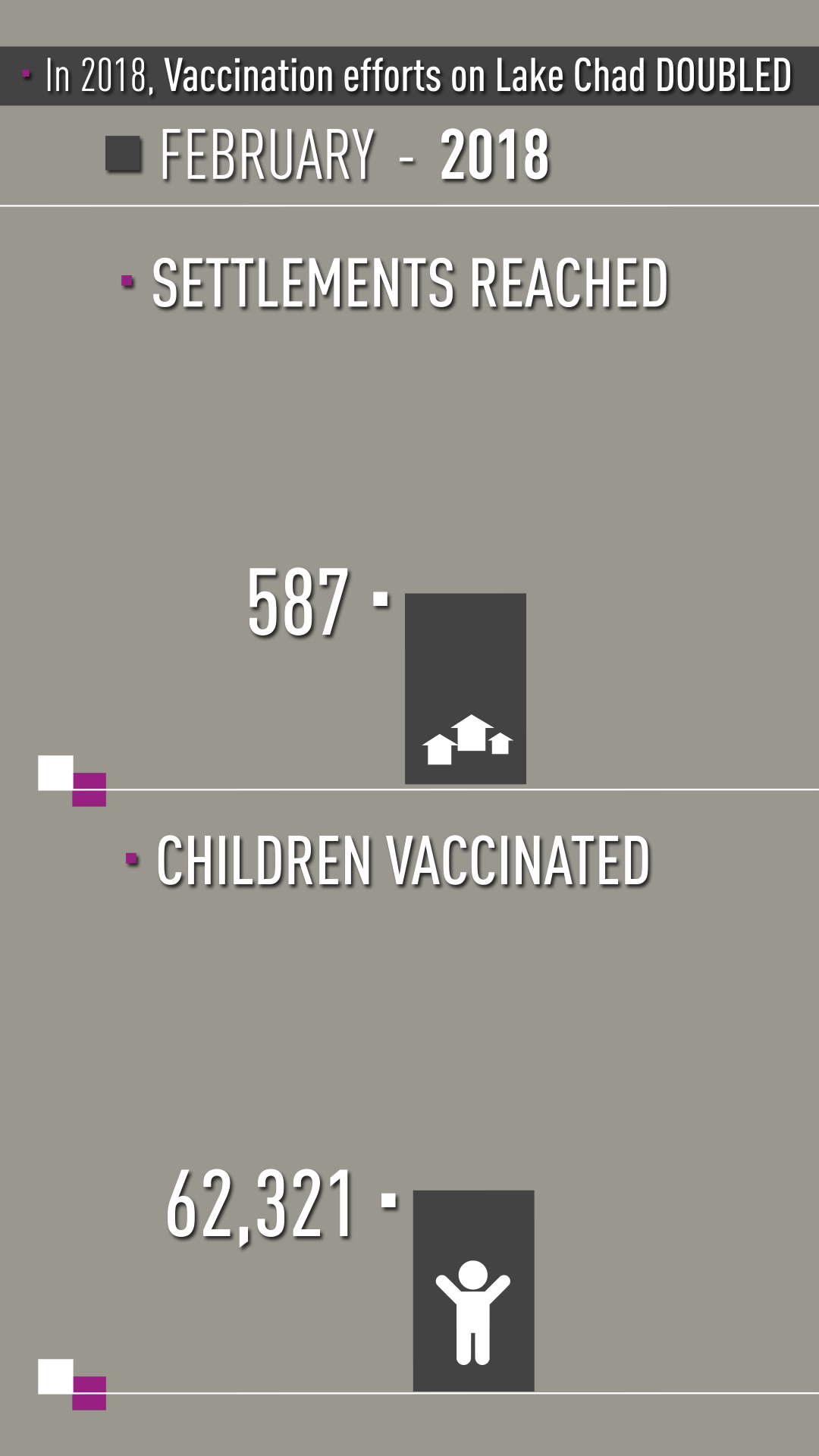

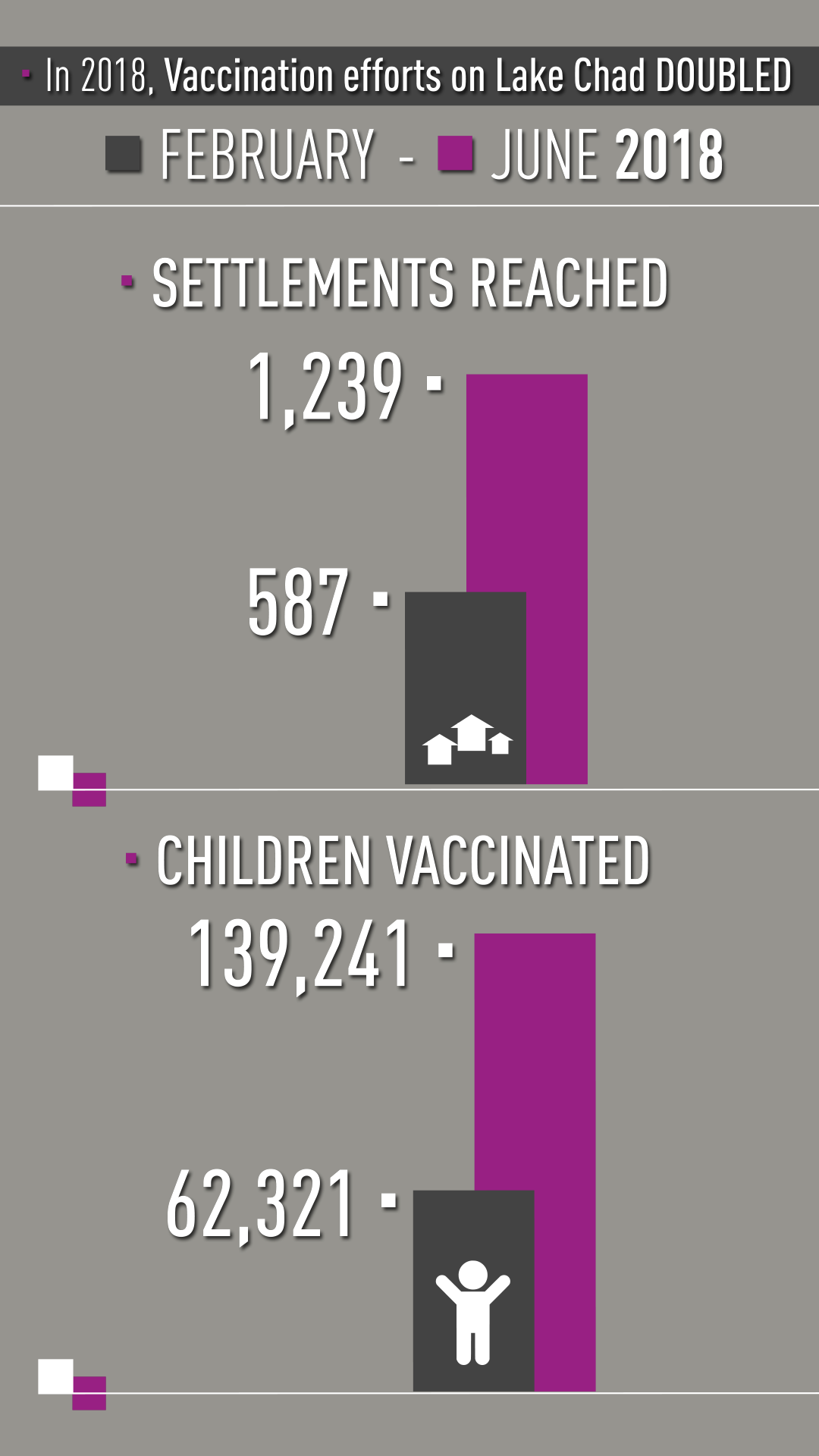

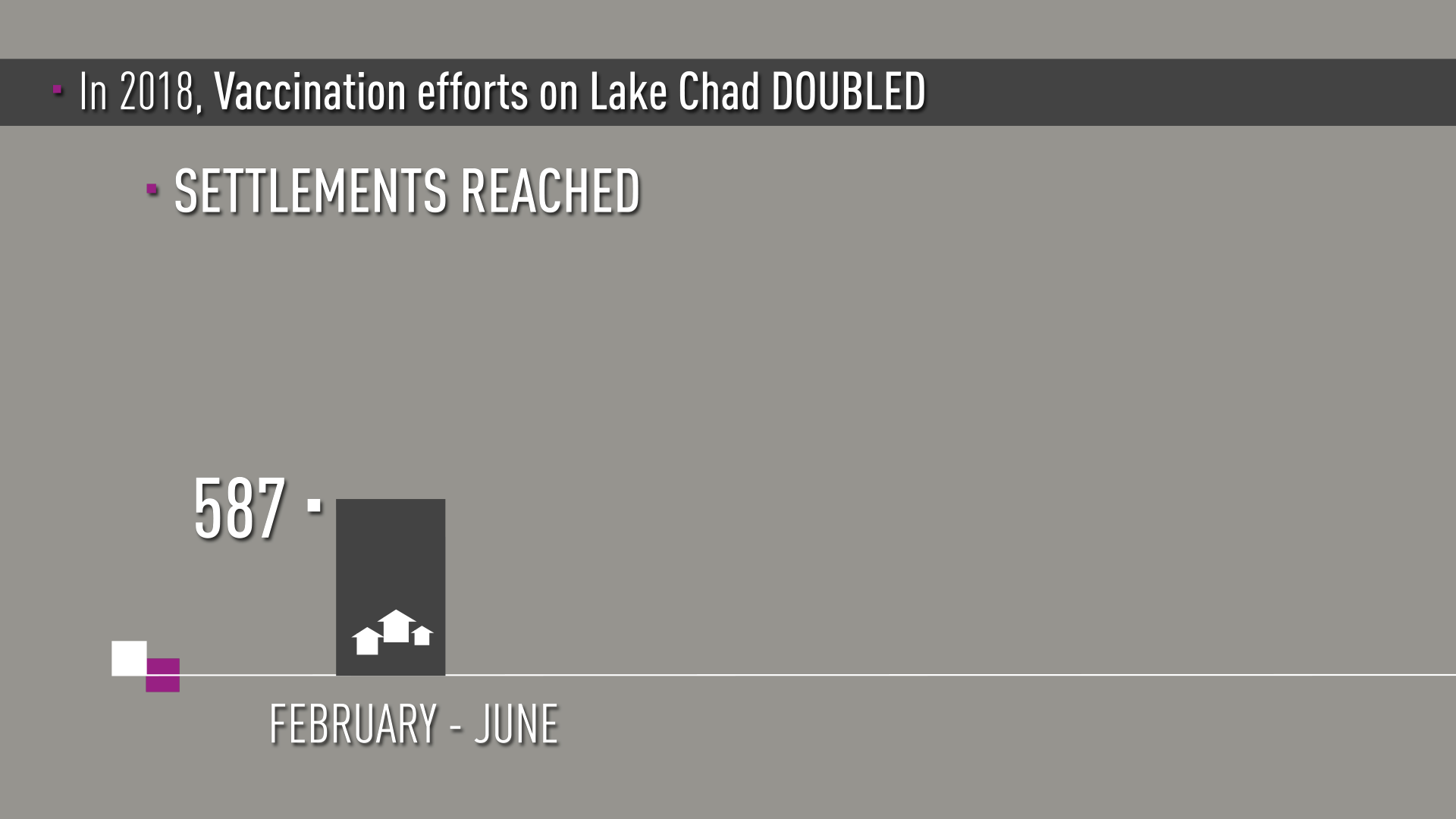

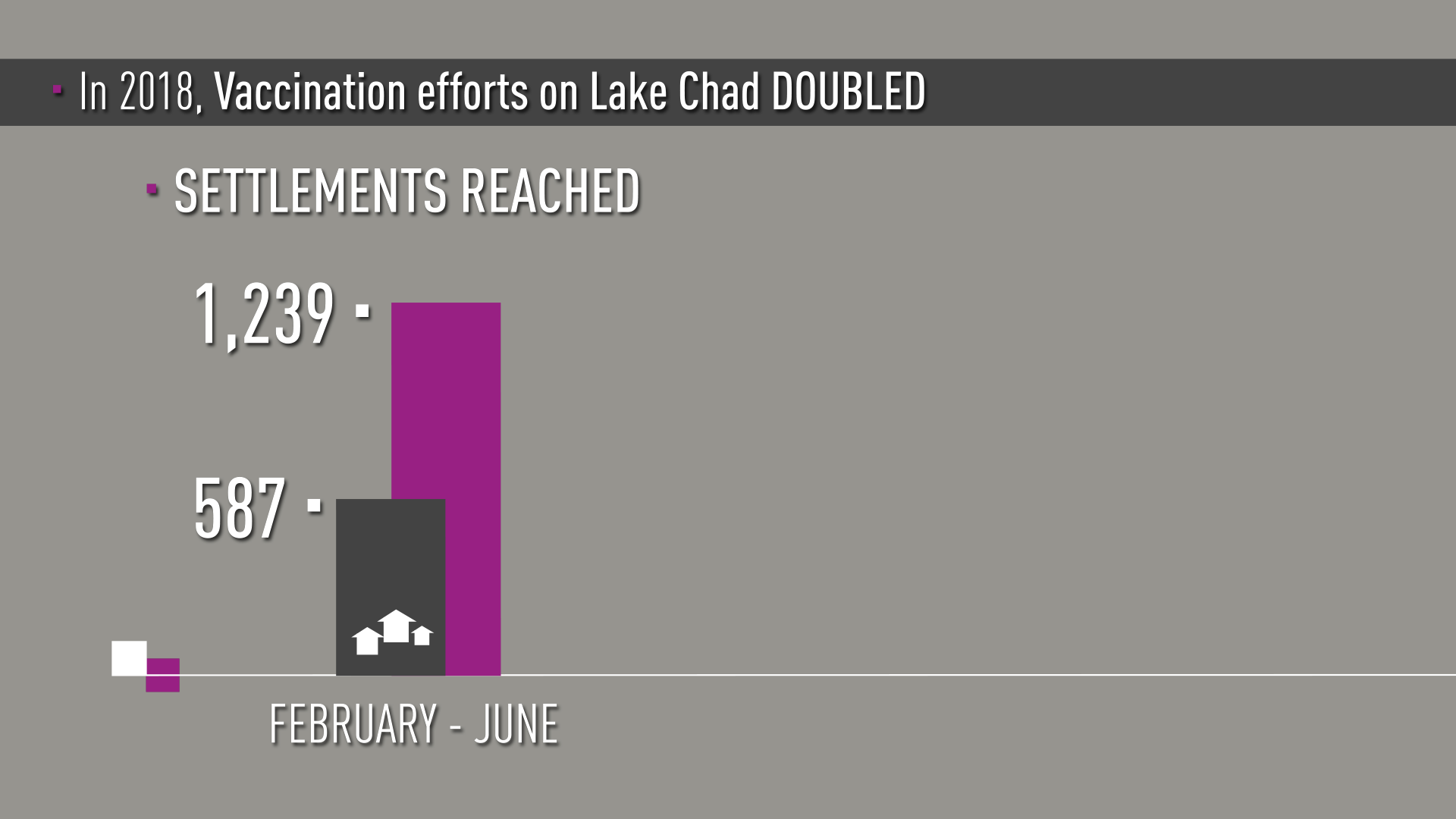

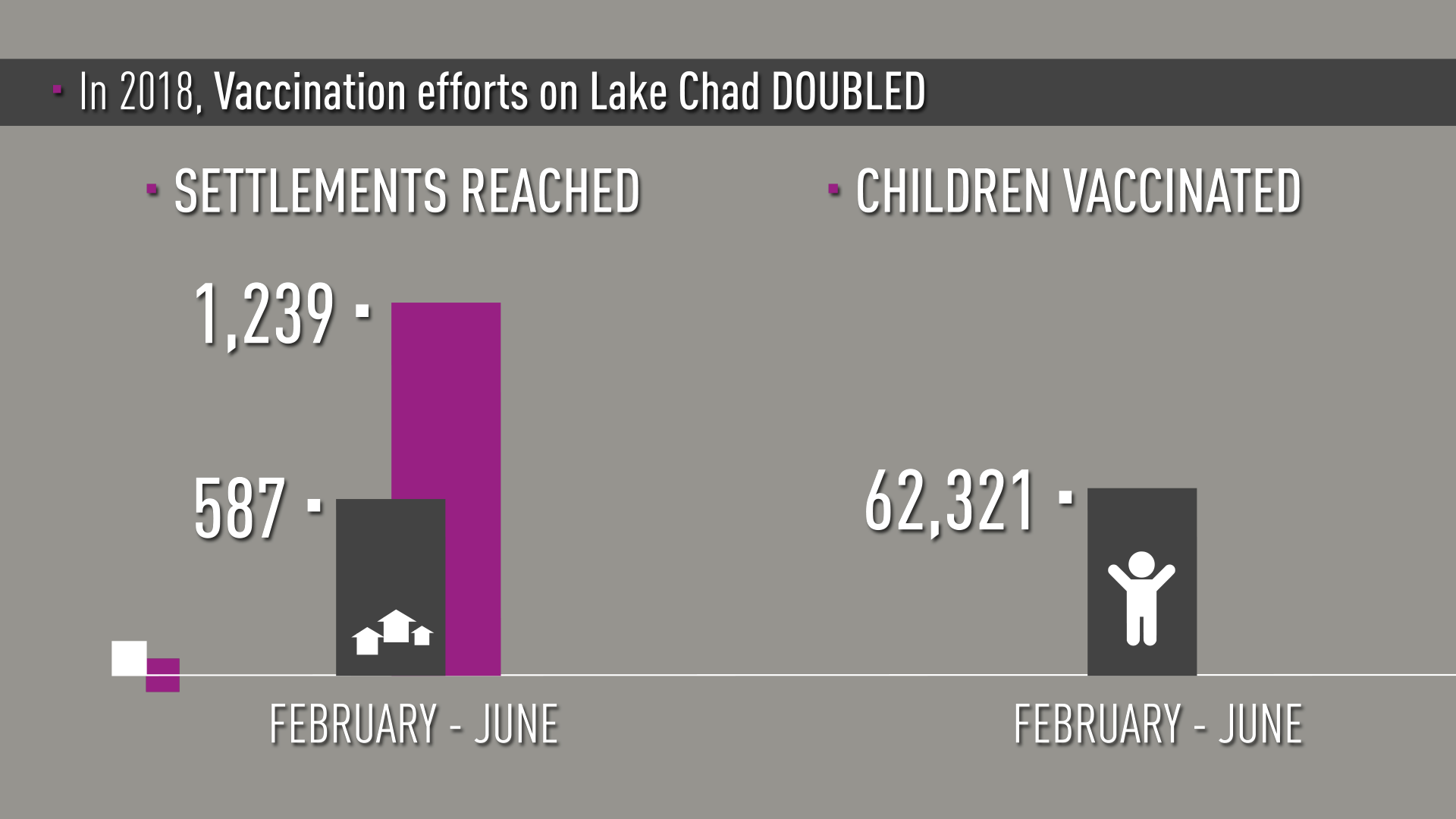

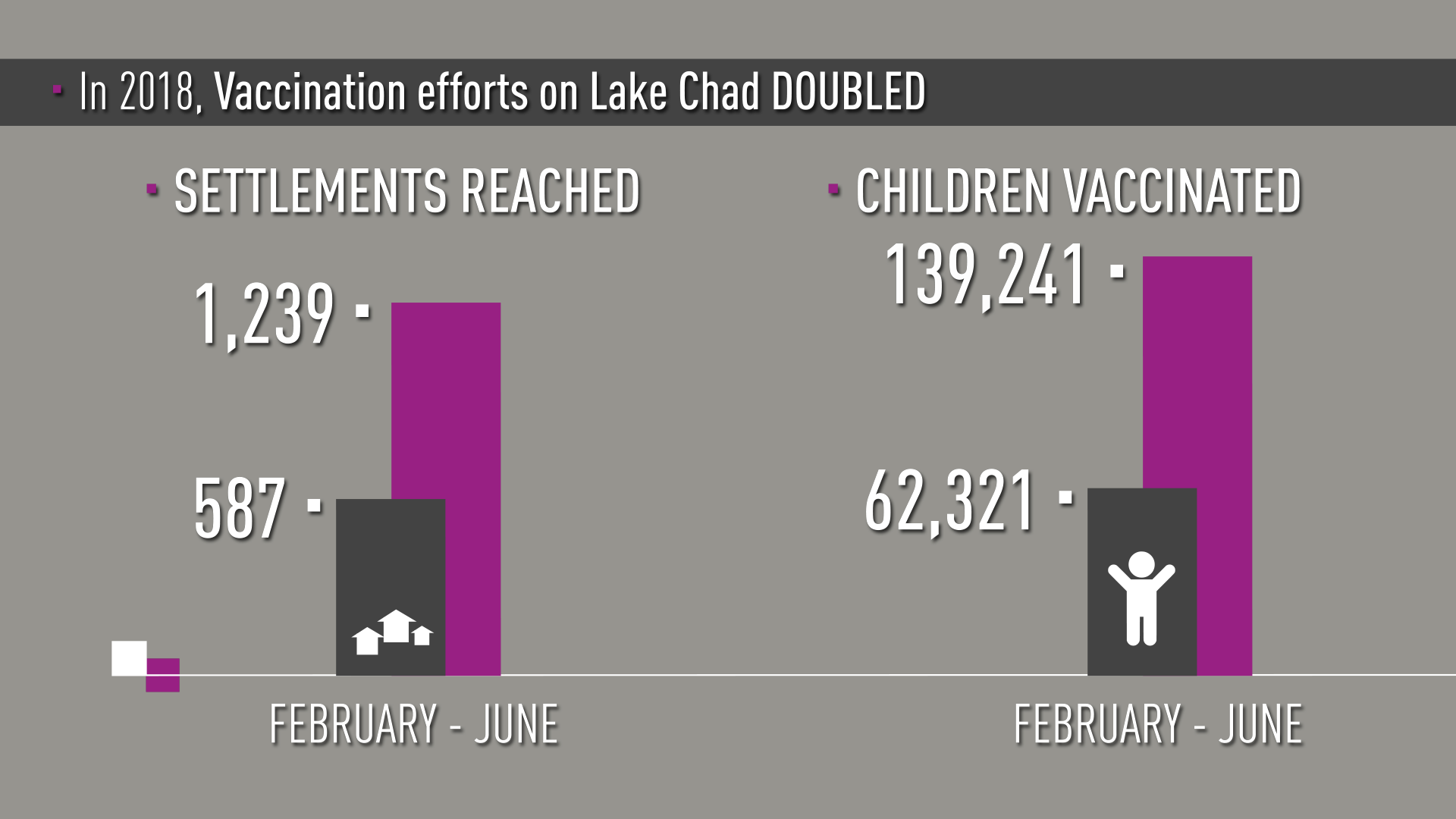

“From February to June 2018 we doubled the number of island settlements and children reached with polio vaccine,” says Dr. Samuel Okiror, the Task Team coordinator.

The numbers are impressive. In February in Bol District where Dr. Aluma worked, 83 settlements were reached and 15,600 children under ten years of age were vaccinated. In June, the campaign reached more than 53,200 children in almost 500 settlements.

The Lake Chad polio response is covering children under ten, rather than the usual age target of under-five. “Too many children were missed over too many years in the island areas of Lake Chad,” explains Dr. Okiror. “We calculated that most children under ten were under-vaccinated when we began this emergency response.”

Map: Google Maps

Map: Google Maps

The threat of poliovirus in the region

Communities living on and around Lake Chad are at a crucible for either an explosion of polio, or, for stopping the virus from any future circulation. The Lake Chad Basin region includes borders with four countries: Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria. Of those, virus from Nigeria poses the most risk.

The last identified wild poliovirus in the area was found in Borno state in Nigeria in August 2016. The northeast part of Nigeria has been affected by conflict for several years as Boko Haram militants have terrorised communities, and the Nigerian army have fought to reclaim territory. As a result, there are “silent” areas for polio – where polio vaccinators can’t regularly travel, and from where possible polio cases aren’t reliably reported.

Vaccinators aim to reach all children under ten years of age with polio vaccine.

Vaccinators aim to reach all children under ten years of age with polio vaccine.

There are also more recent cases of circulating vaccine-derived polio viruses (cVDPVs) identified in 2018. These viruses emerge - very rarely - when weakened poliovirus strains within the oral poliovirus vaccine regain the ability to cause paralysis. This happens typically in areas where vaccination coverage and sanitation are poor, and the vaccine virus can travel from child to child over many months, transforming into a type that causes paralytic polio.

“The polio threat to communities in the Lake Chad Basin area definitely arise from detection of polioviruses in Nigeria,” says Dr. Okiror. “That’s why we have tackled the Lake Chad polio activities on an emergency basis."

"As we work to end polio in Africa, we simply can’t afford new outbreaks of polio in countries like Chad. We do everything with a view to lock down any gaps where polio could emerge.”

Doing the hard work

Dr. Adèle Aluma and her colleagues have long, often gruelling days out in the field.

“On campaign days we start at the crack of dawn because we have to travel so far,” she says.

To help build stronger local ties, they've identified a list of community leaders and their phone numbers. Team members call the leaders before a campaign to tell them to expect vaccinators and advise them to call if the vaccination teams don’t arrive.

Meeting with community leaders.

Meeting with community leaders.

Dr. Aluma says demand for vaccination is high. She recalls spending all day travelling to one island health centre. She and the vaccination team arrived so late and exhausted, they had to go straight to bed.

“At 6 in the morning we woke to find the entire community of women and children at the health centre, waiting for the vaccine.”

Dr. Aluma says due to this demand, the teams offers the full complement of routine vaccination services whenever they can.

“We think that if we are going to travel so far, we should go with all vaccines.” She also notes that in order to end polio, children should also receive one dose of inactivated polio vaccine.

Ending Polio

The progress on the Lake Chad islands has been remarkable. The efforts of people like Aluma and her colleagues has resulted in reaching some of the most marginalised children of the world and providing, for many, their first contacts with a health system.

“When we make contact with children for polio and routine vaccination,” says Dr. Okiror, “it proves we can reach these families with more health services.”

“Thousands of health workers and volunteers are tirelessly working to cross very difficult terrain and reach children who have never been reached,” says gOkiror. “They are working hand-in-hand with communities.”

Dr. Okiror says the efforts must be sustained until the African region is certified as polio-free. “We’re at a phase now where we need continued resources to reach these children,” says Dr. Okiror. “We’ve always said that the last mile of polio eradication is the most difficult. Here in the Lake Chad Basin, this couldn’t be more true.”

“Together we shall confine the polio virus to the history books where it belongs.”

Acknowledgements

Our World United to End Polio project is the result of a collaboration of the United Nations Foundation, with partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

Christine McNab, an independent multimedia producer specialising in global health and development, produced the series. The project was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

OVERALL PRODUCTION

Executive producer, photographer, writer, narrator: Christine McNab

Video editing: Kathryn Dickson, OnFireFilms.tv

Graphic design and animation: Ron Sloan

Music, Re-recording Mixer: Michelle Irving, Soleil Sound

Sadia Shakeel (centre, pink scarf) at a Rotary-funded resource centre for health workers.

Sadia Shakeel (centre, pink scarf) at a Rotary-funded resource centre for health workers.

Community-based Vaccinators in Pakistan

Camera and sound: Haider Ali

With special thanks to:

Several people at Rotary PolioPlus Pakistan in Karachi including Aziz Memon, Alina Visram, Qaiser Shahzad, and Sadia Shakeel.

Naureen and many of her colleagues who helped to tell the story.

WHO Pakistan and UNICEF Pakistan.

Camerawoman Esther Verkaik, near Streefkerk.

Camerawoman Esther Verkaik, near Streefkerk.

Lessons from a Poliovirus Spill

Camera and sound: Esther Verkaik

With special thanks to:

Dr. Erwin Duizer and his colleagues at RIVM, the Netherlands.

Cameraman Stefan Randström records Dr. Nguemela Macair at the Dar es Salaam refugee camp.

Cameraman Stefan Randström records Dr. Nguemela Macair at the Dar es Salaam refugee camp.

Chad: Across the Sands and Chad: Across the Waters

Camera and sound: Stefan Randström

With special thanks to:

The Lake Chad Polio Task Team, including Dr. Sam Okiror and Jonas Naissem; Adbel Aziz Kadai, UNICEF C4D Consultant

Lake Chad PolioTask Team consultants including Dr. Adèle Daleke Lisi Aluma, Dr. Aimé Matela, and Dr. Nguemela Macair;

Nurse Awandi Epainette

The many Bol and Bagasola District officials who helped ensure we got where we needed to go.