Proving the Possible

Lessons from Peru, Europe and India

Our World United to End Polio profiles individuals from around the globe who have committed their expertise, time and passion to the historic, world-wide effort to eradicate polio. It's a journey that began in the Americas in the 1980s, has crossed every continent, and is now focussed on a handful of countries still facing polio outbreaks.

In this immersive series, engage with photos, videos, animation and stories about people who have given everything to end a disease.

Meet Dr. Roger Zapata, a Peruvian paediatrician who risked his life to investigate what turned out to be the last case of polio in the Americas.

Dr. Roger Zapata

Dr. Roger Zapata

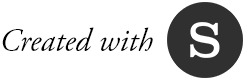

Dr. Harrie van der Avoort describes the weekend he made an unexpected discovery.

Dr. Harrie van der Avoort

Dr. Harrie van der Avoort

Learn how Dr. George Oblapenko, a Russian epidemiologist, created a cross-continental partnership to end polio in Europe.

Dr. George Oblapenko

Dr. George Oblapenko

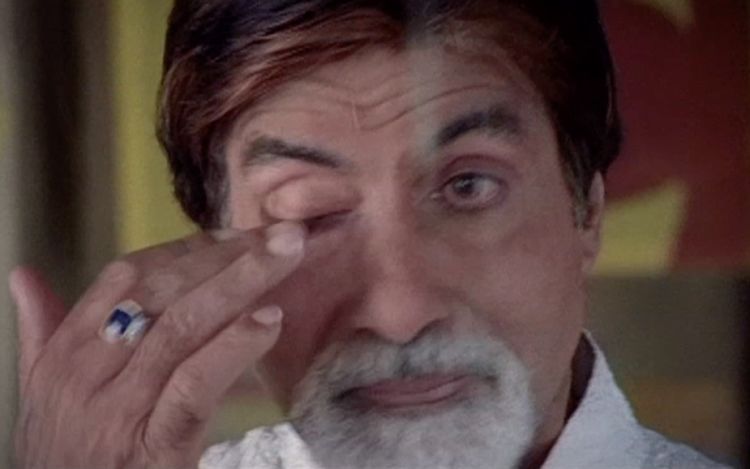

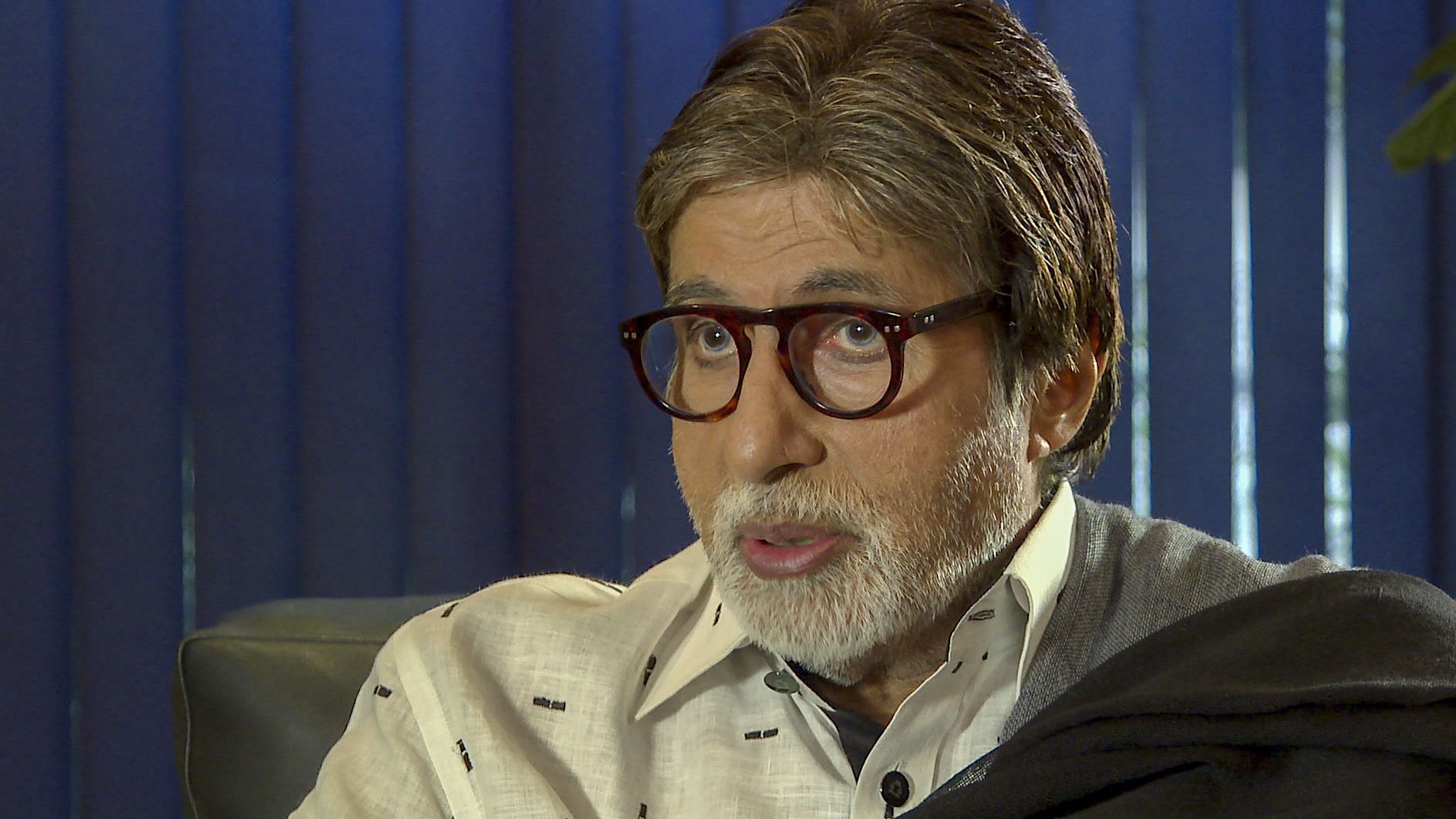

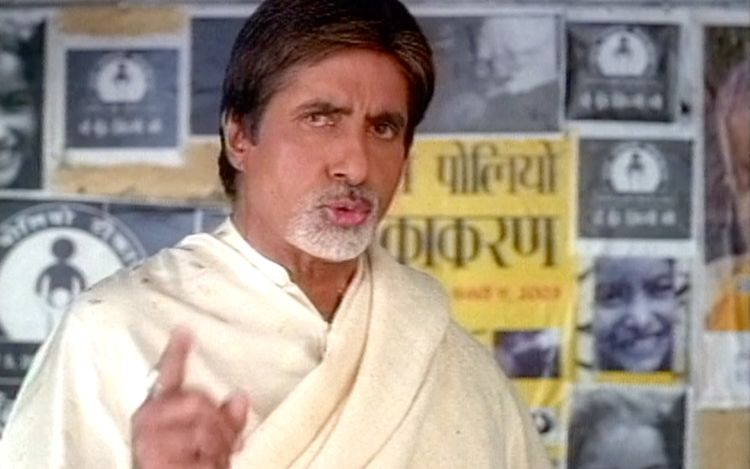

Find out how Indian film legend Amitabh Bachchan turned a simple tagline into a national mantra.

Mr. Amitabh Bachchan

Mr. Amitabh Bachchan

To experience these stories, simply scroll down.

To skip to a different story, click a headline in the menu bar.

Luis

The First Last Case

Ending Polio in Peru

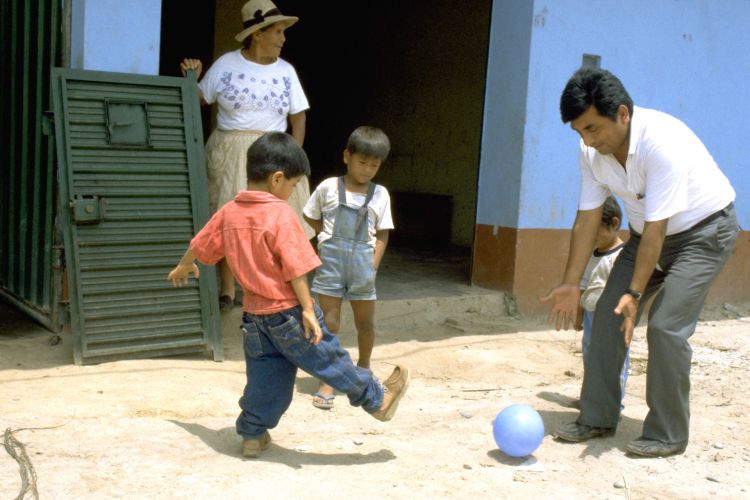

As the jungle slips past, Dr. Roger Zapata sits in a white van, transfixed by memories from long-ago, when he frequently travelled this road to Pichanaki.

“There were ambushes and kidnappings on this road,” remembers Zapata. “To come here we had to be bold, and a bit crazy.”

Dr. Roger Zapata, on the road to Pichanaki, Peru in June 2018.

Dr. Roger Zapata, on the way to Pichanaki, Peru in June 2018.

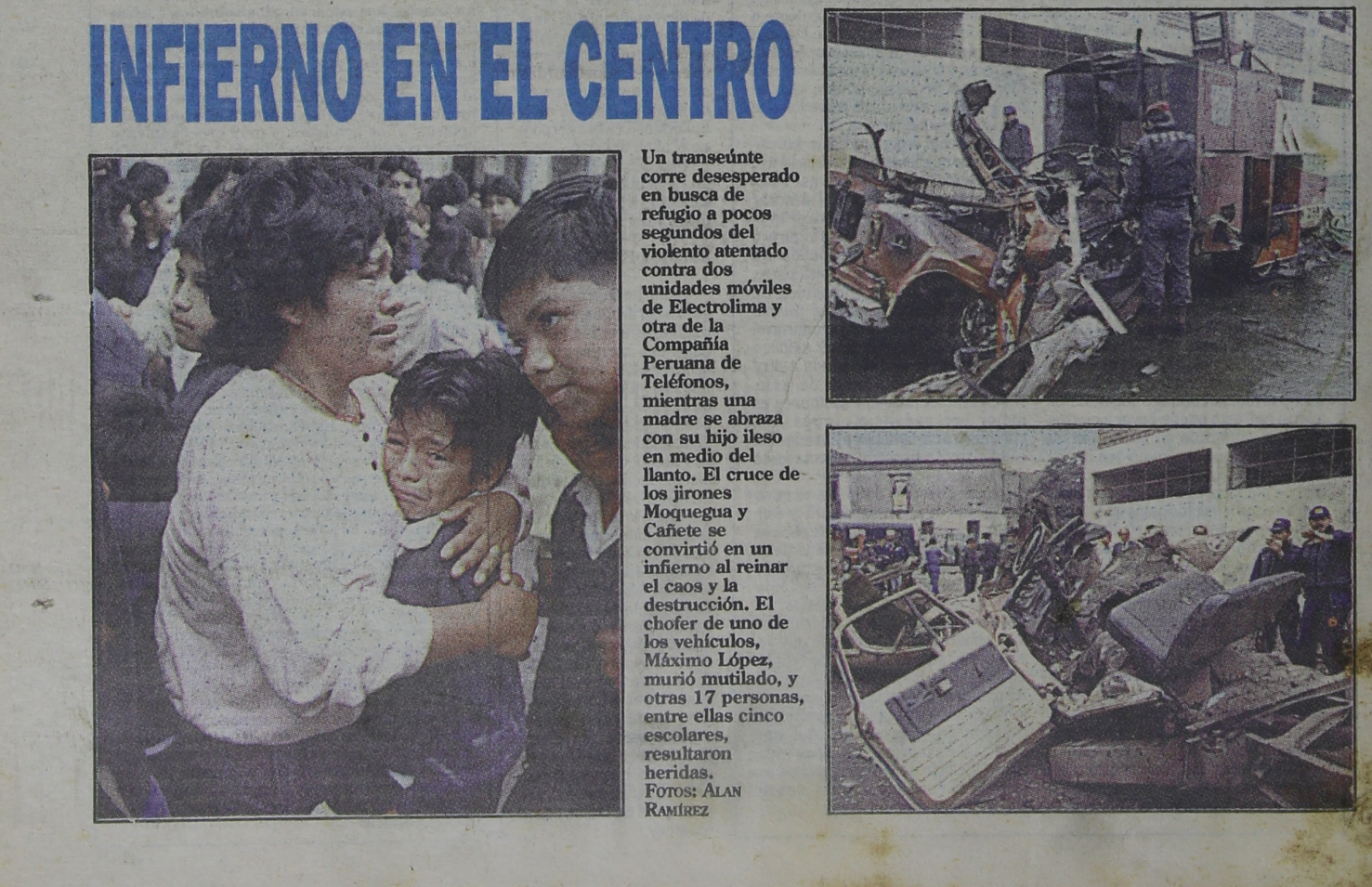

The late 1980s and early 1990s in Peru was the time of the Sendoro Luminoso – the Shining Path – a bloody resistance movement aimed at replacing Peru’s government with a communist revolutionary command. Peruvians refer to the period as a time of pure terrorism.

Newspaper headlines from August 1991, the month Zapata travelled to Pichanaki to investigate a probable polio case.

Newspaper headlines from August 1991, the month Zapata travelled to Pichanaki to investigate a probable polio case.

One of their tactics was to ambush cars, steal the contents, kidnap, or kill the inhabitants . Health centres were bombed. Ministry of Health vehicles were stolen and pushed over cliffs.

Zapata says he was a bit scared that day in August 1991, when he had to investigate what was a probable polio case in the town of Pichanaki. It was a ten-hour drive from Lima over the Andes, and it was an active Shining Path area.

“It was my job to go,” explains Zapata. “So the driver and I got in our little blue car, known as ‘the vaccine car’, and we made our way to Pichanaki.”

As the jungle gave way to the high Andes, Zapata didn’t know he’d be meeting the last person to be infected with wild poliovirus in all of the Western Hemisphere.

Here, watch a video of the story of Roger Zapata and Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez, or scroll on to read more.

Roger Zapata and Luis Fermin meet for the first time in year, and Luis discovers why he was infected with polio.

In 1991 Zapata was part of team of consultants working for the Pan American Health Organization’s (PAHO) Peru office.

His job was to help establish surveillance systems and immunization campaigns required to end polio in Peru. This was part of a continent-wide strategy adopted by PAHO’s 35 member-states in 1985. The goal was to stop polio transmission in the Americas.

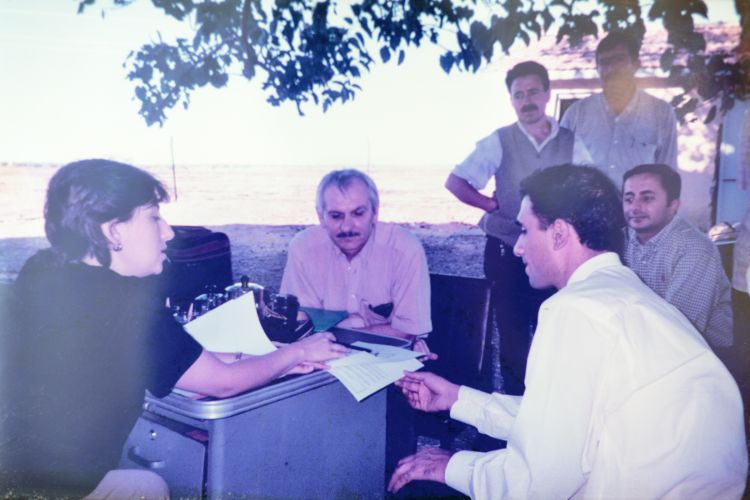

Peru's polio team.

Peru's polio team.

It was challenging work. The mountainous terrain, altitude and windy roads, combined with the threat of the Shining Path made for dangerous days. In the town of Pichanaki, where Zapata would travel to investigate that polio case, he says it wasn't uncommon to see "one, two or even three bodies piled on top of one another, with a sign beside them reading 'traitor', or 'whistleblower.'"

These were a warning from the Shining Path.

People in Lima wonder why anyone would want to drive to Pichanaki.

The journey is arduous. From Lima at sea level, a serpentine road climbs almost 16000 feet (5800 metres) across the high Ticlio pass. The air is thin and the chance of nausea is high due to the serpentine roads and the lack of oxygen.

Travellers are at risk of rock and mudslides, sheer cliff drops, long delays due to transport truck breakdowns, and endless construction.

For about an hour, the vast high Andean landscape is pitted with huge machinery, zinc and copper mines and the villages of people who work in them. And then, it’s a steep descent to Pichanaki through Peru’s selva alta, or high jungle, where there are endless trees, rivers, waterfalls and coffee shrubs.

After a 10-hour journey Zapata arrives in Pichanaki, for the first time since 1991.

He spots Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez in the town square. They smile and walk towards one another. “Hey, Luis! How are you?! Look at you!”” They hug hello and then sit together on a bench. They chat.

Zapata tells Cortez about the first time they met, when he was a toddler. Zapata had examined Cortez, and confirmed that he indeed had polio.

Zapata, of course, remembers Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez very well. He's the reason he risked his life to come to Pichanaki in 1991.

They talk about a rather famous photo taken in 1991. At least, it's famous in public health circles. "This picture was made known around the world because it told the story of the journey towards polio eradication. It shows you as the last case in the Americas," Zapata explains.

Zapata holds Cortez's hand in a photo taken in 1991. The woman beside Luis is his adoptive grandmother. The photo came to symbolize the certification of the Americas as polio-free. Photo PAHO.

Zapata holds Cortez's hand in a photo taken in 1991. The woman beside Luis is his adoptive grandmother. The photo came to symbolize the certification of the Americas as polio-free. Photo PAHO.

The image, taken by a photographer from the Pan American Health Organization, has been used extensively to promote the certification of the Americas as polio-free, an achievement earned in 1994.

Cortez says he’s glad his photo was a bit famous. Though it’s fair to say that polio, rather than fame, has had more impact on his adult life.

Luis Cortez was abandoned as a baby.

Some say he was left at a church. Others say he was left at the local bar. Luis himself says he was left in a park. A local woman took him in. She already had children. His adoptive mother died in 2016, and he says, his adoptive siblings have rejected him.

Cortez now lives with Felicita Aliaga. In exchange for a room, he helps out in her shop on Pichanaki’s main road, where she also offers toilets and showers to people for a small fee. She is kind to Luis, and he says he appreciates her help.

Cortez works in a shop where people can also pay to use toilets.

Cortez works in a shop where people can also pay to use toilets.

Cortez worked at a restaurant for some time, but due to the pain in his leg, he can’t stand for long periods of time, and he had to give up that work.

“I think of polio as a really ugly disease. I cannot walk properly. Getting a job is difficult because people discriminate against me.” He says this with sadness. There is no malice or anger.

There are stories about why Cortez was paralysed by polio.

In 1991, before Cortez, Peru had recorded just one other polio case. The only other country in the Americas with polio that year was Colombia. The pressure was on to finally stop transmission.

Disruptions and violence caused by the Shining Path, who were based outside the main cities, created distrust between the authorities and rural people. One widely-shared idea of why Cortez was infected with polio was that the Shining Path had destroyed the Pichanaki health centre, and he couldn't complete his vaccinations.

Roger Zapata says that wasn't the case, as he remembers the hospital being operational at the time. That's where he examined Cortez.

To understand more about Cortez's polio infection, he and Zapata go to visit Joaquin Delgado. He was the immunization nurse in 1991, and remarkably, still works as a nurse in Pichanaki.

Nurse Joaquin Delgado greets Cortez and Zapata. He hadn't seen Zapata since 1991.

Nurse Joaquin Delgado greets Cortez and Zapata. He hadn't seen Zapata since 1991.

Joaquin Delgado smiles and hugs Zapata and Cortez. The three haven’t met together since 1991. They sit on a bench in a courtyard and talk about the early days.

Delgado remembers meeting Luis for the first time. “His mother brought him to us because he had difficulties walking. We advised her to take him to Lima where doctors first diagnosed him with polio.” Shortly after that, as per the polio program’s surveillance protocols, Zapata travelled to Pichanaki to investigate and he confirmed the diagnosis.

Cortez asks Delgado why he got polio.

Cortez says he was vaccinated against polio. And, he says, he believes he was infected with poliovirus because there was a problem with an injection. That’s what his adoptive mother told him.

Roger Zapata says that after Cortez became sick with polio, which would have caused a fever and maybe a sore throat, his mother probably took him to a local pharmacy where he was likely treated with an injection for the fever. Soon after, young Luis developed paralysis. His adoptive mother blamed that injection.

Joaquin Delgado’s voice is gentle as he delivers the news. “Luis Fermin,” he says, “you got polio because you didn’t receive all three doses of oral polio vaccine. You had only one dose.”

Cortez’s voice breaks, and he challenges Delgado. “But how do you know this is true Joaquin?” Delgado tells him he knows because he was there. He remembers that when the polio vaccination teams went house-to-house, Luis’ adoptive mother had refused the vaccine for Luis. “It happened sometimes,” Delgado says, “they were hard times. People were mistrustful and afraid.”

So, Cortez was infected with polio because he wasn’t fully vaccinated. The vaccine was available, but his adoptive mother didn’t accept it for him. It's impossible to know what she was thinking at the time. People say trust was a rare commodity in those days when the Shining Path constantly threatened violence.

But now, for the rest of his life, Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez has to live with a leg that doesn’t move properly, with pain, fatigue, and with discrimination.

Joaquin Delgado says Cortez got polio because his adoptive mother didn't accept for him to finish the doses required. He says there was a lot of mistrust during the Shining Path years.

Joaquin Delgado says Cortez got polio because his adoptive mother didn't accept for him to finish the doses required. He says there was a lot of mistrust during the Shining Path years.

Cortez received care after his diagnosis. Gustavo Gross, a senior Rotarian who led the charge to raise funds for polio eradication in Peru, arranged for him to move to Lima. Rotarians paid for Luis to have rehabilitation and schooling.

“The happiest time in my life was my childhood,” remembers Cortez. He liked to play soccer with other kids. “When I was young, I didn’t notice the polio so much,” he says. “It’s now when I’m an adult that my life is quite hard.”

Cortez's diagnosis triggered a massive, house-to-house polio campaign.

Dr. Roger Zapata remembers this as an impressive period, when nurses, teachers and mothers were mobilized to help.

“We worked with UNICEF on this. The teachers were leaders in their communities. They were trained to help with vaccination and also with identifying cases of acute flaccid paralysis.”

The vaccination team combed the mountains, up and down muddy jungle paths, to find children to immunize.

“Sometimes you were walking and were halfway to the community and the rain started so you couldn’t reach the place. You had to go back or postpone the visit and then try again. Sometimes we lost our shoes and had to go barefoot,” says Delgado.

Roger Zapata and Joaquin Delgado reminisce about the polio campaigns that ended polio in Peru and the Americas.

Roger Zapata and Joaquin Delgado reminisce about the polio campaigns that ended polio in Peru and the Americas.

It took three years of this kind of persistence to end polio in Peru. Health authorities could then confirm that Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez was the last person to be paralysed by indigenous polio virus in Peru, and in the Americas.

On August 21 1994, a group of polio leaders representing the partnership celebrated the end of polio in the Americas. The International Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication found that Peru, and all countries in the Americas, met the criteria to demonstrate that polio no longer circulated in the Western hemisphere. It was a big day.

In Peru, there was a celebration in Pichanaki. Leaders from the polio partnership - the Ministry of Health, Rotary, UNICEF, PAHO and USAID, traveled to Pichanaki in a helicopter. They had a celebratory lunch and toasted the end of a disease.

In Pichanaki on his June 2018 visit, Roger Zapata asks Joaquin Delgado what he thinks of what they achieved. “Imagine,” he says, “27 years without a single case of polio.”

“We faced so many barriers and difficulties,” says Delgado. “But we really worked with strong hearts. We were so committed.”

Zapata asks Cortez the same thing. “What do you think Luis?” he says, “how did we do?”

Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez is not a doctor, but he perhaps knows polio better than anyone.

On this day of recounting powerful memories of commitment and bravery, his words ring the loudest.

“Polio is a horrible disease. Horrible. Eradicating polio is so important. No one should suffer polio. Ever.”

A Polio Outbreak

in Europe

The Netherlands 1992

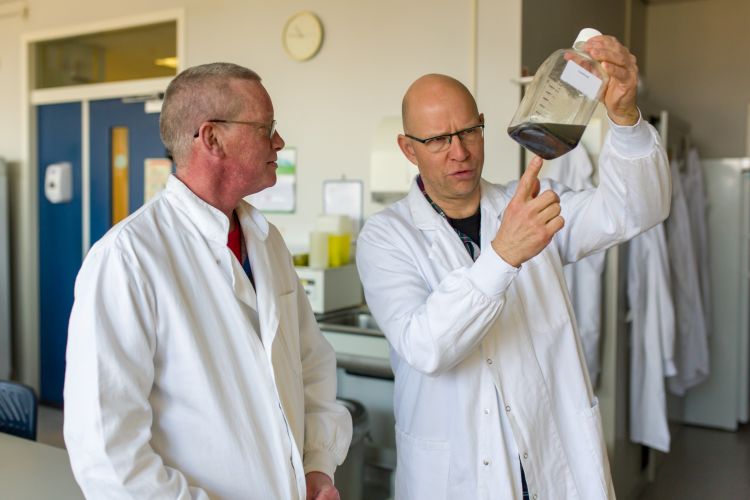

On a Friday afternoon in mid-September 1992, Dr. Harrie van der Avoort was preparing to finish work for the day at his laboratory in Bilthoven. Then he received a phone call.

“My boss called me to tell me there was something wrong in the Bible Belt. There was a 14-year old boy with paralysis who was not vaccinated. They suspected polio.”

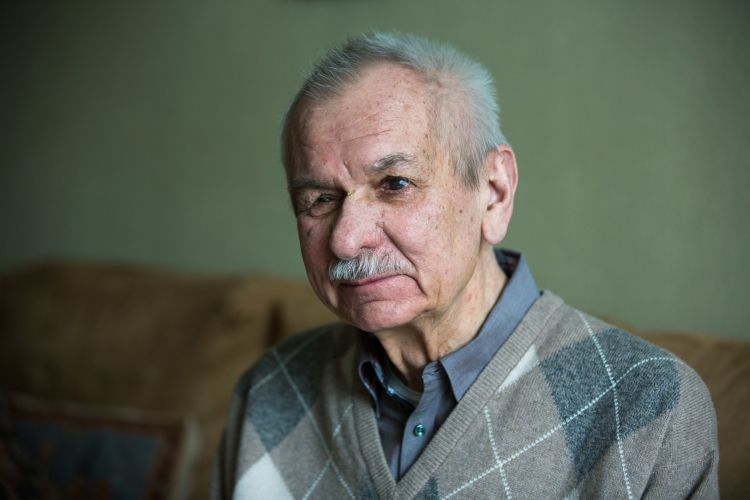

Dr. Harrie van der Avoort, the retired head of the Dutch National Polio Laboratory.

Dr. Harrie van der Avoort, the retired head of the Dutch National Polio Laboratory.

Dr. van der Avoort buttoned his laboratory coat. It was going to be a late night and probably a long weekend at the RIVM, the Netherland’s National Institute for Public Health and the Environment.

Watch a video about the Dutch polio outbreak below, or continue scrolling to read more.

Learn more about Dr. Harrie van der Avoort's unforgettable weekend, back in 1992.

“The polio group gathered immediately, and we made a checklist of what was required. We needed extra fresh cell culture tubes, media for inoculation of stool samples and reagents for molecular testing. We put everything into place and went to work on the samples as soon as they arrived in the lab.”

Dr. van der Avoort, now retired, is a biochemist. In 1991 he was charged with updating the RIVM polio laboratory with the newest molecular methodologies for polio diagnostics. It was part of an effort to create a global polio laboratory network that could not only diagnose polio but also show how polioviruses travelled across borders and around the world.

That weekend in 1992, van der Avoort and his team worked day and night to put those new methodologies to work.

“Within 48 hours we could show that three of the younger siblings of the patient were infected with polio. That was enough to start the whole polio outbreak management in the Netherlands.” - and, in the world.

Polio: silent and fast

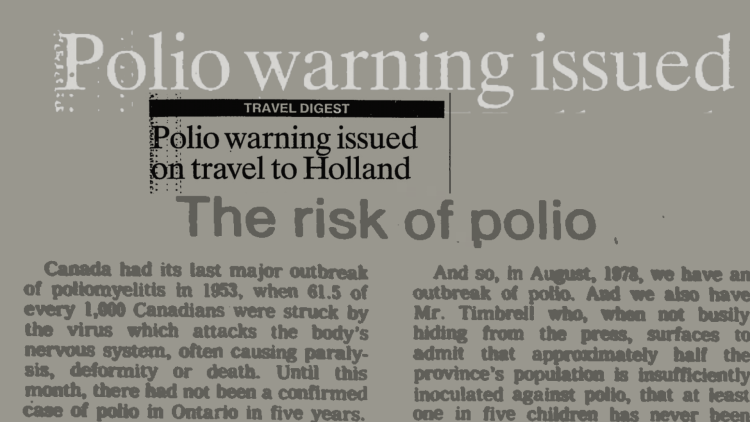

“We had to alert the World Health Organization right away,” remembers van der Avoort. “We were worried about a repetition of the polio epidemic in 1978.”

Polio is usually only detected when someone shows signs of paralysis. This can be as few as one in 500 or even 1000 infected. Otherwise, it spreads silently.

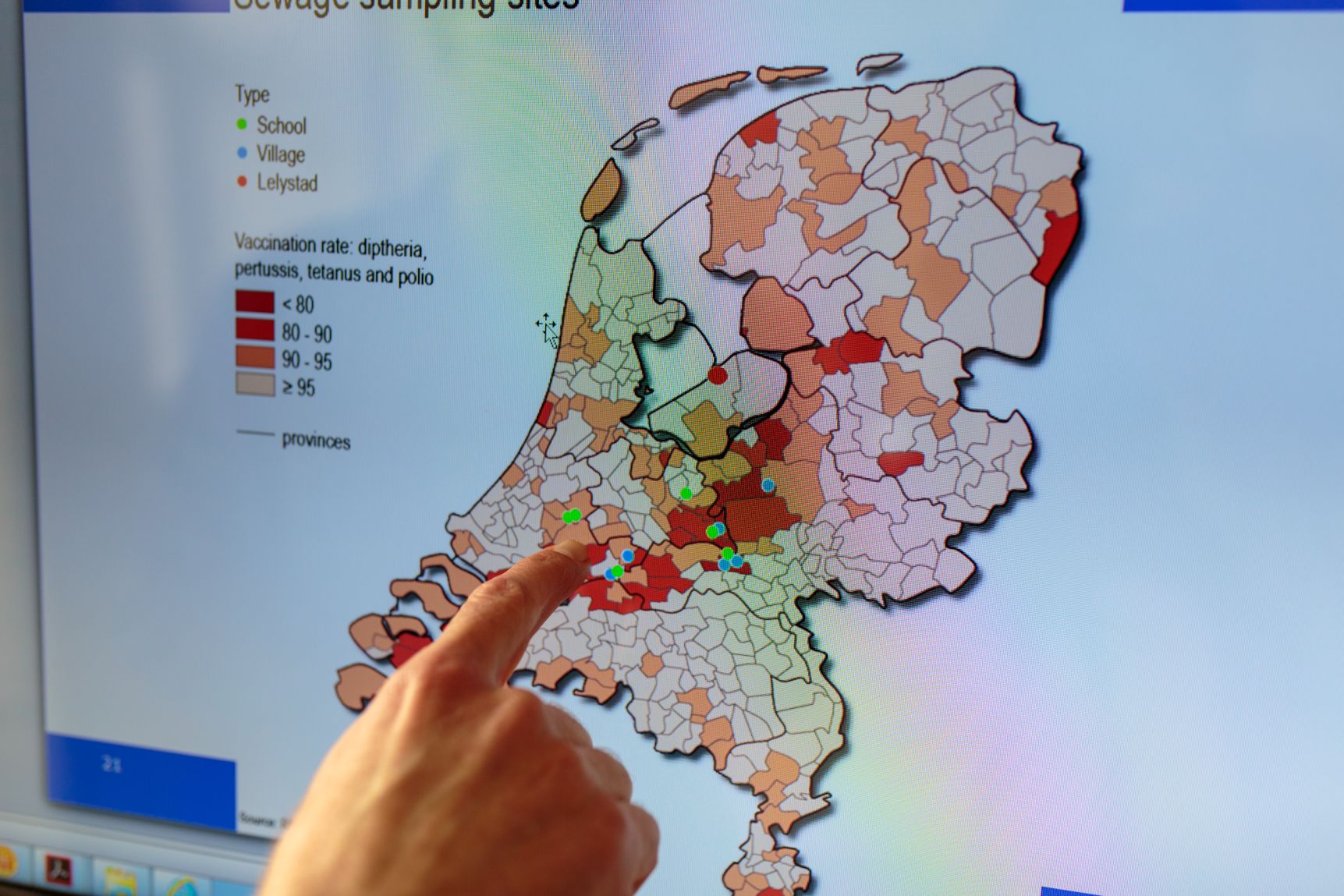

When people aren’t immunized, are grouped closely together and sharing toilets and water, poliovirus can infect everyone who is not vaccinated. These conditions exist in the Dutch “Bible Belt” of the Netherlands, a band of territory running from central to the south-western Netherlands.

One way to identify the area on a map is to look at the pattern of vaccination coverage, where darker colours indicate low immunization uptake. Tens of thousands of Orthodox Protestants who live in the Bible Belt have refused vaccination over the years and are susceptible to polio and other infectious diseases.

The areas in deeper orange and red indicate the area of the "Bible Belt," where vaccination coverage is lower than the Dutch average.

The areas in deeper orange and red indicate the area of the "Bible Belt," where vaccination coverage is lower than the Dutch average.

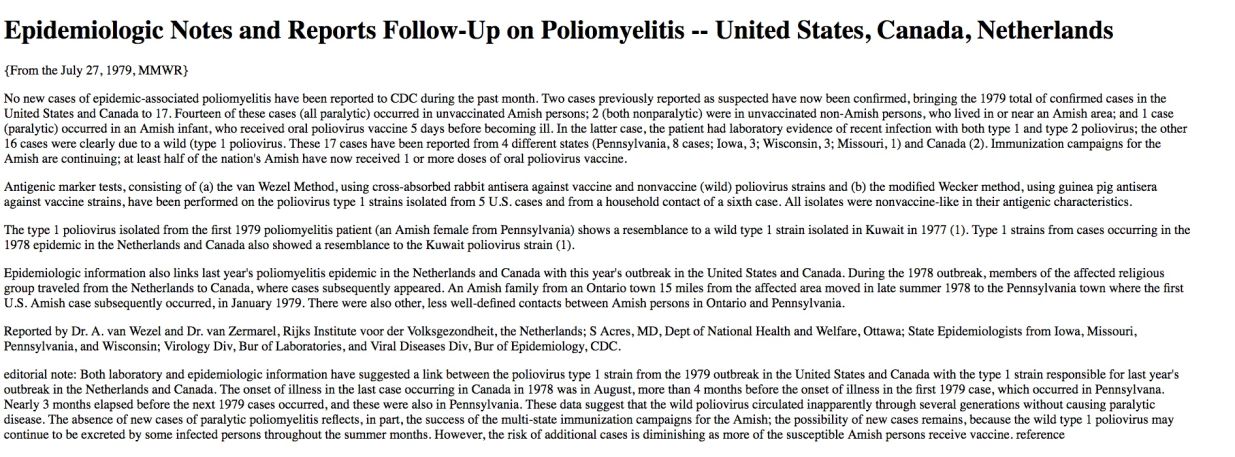

In the 1978 outbreak, the first polio cases originated amongst Orthodox Protestant families in Elspeet, a small country town. There were 110 cases.

In typical silence, and probably through international travel between communities, the outbreak spread from the Dutch Bible Belt to Canada and then to the United States. In 1978 and 1979, polio caused 11 cases of paralysis in Canadian Dutch Orthodox communities in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia. There were 15 cases in the US States of Iowa, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Ten of those affected were paralysed.

The CDC's report following the 1978 polio outbreak in the Netherlands.

The CDC's report following the 1978 polio outbreak in the Netherlands.

A nascent polio laboratory network including the US Centers for Disease Control made the connection between the Netherlands and North American outbreaks.

How to protect communities in 1992?

Given the evidence from 1978, van der Avoort was right to be concerned in 1992.

Poliovirus from the Netherlands indeed travelled to Canada. With public health laboratory networks on high-alert, Canadian services detected 22 poliovirus isolates from a small orthodox community in southern Alberta, the same place where one case of paralysis had occurred in 1978. Genetic sequencing showed they were linked to the Dutch outbreak as a result of international travel. Luckily, no one was paralysed.

In the Netherlands, the New Scientist reported a “Dutch Panic” over the outbreak, and demand for the polio vaccine was so high that supplies were depleted. There were reports of clinics offering night-time services so that families could be vaccinated under the veil of dark.

The Netherlands' 1992/1993 outbreak lasted for about six months and 71 people were diagnosed with polio. All but one was part of the Orthodox community, and none of them were vaccinated. Fifty-nine people were paralysed.

“Two of the patients died. The oldest patient was 68, and the youngest was a baby of just 14 days old. It was tragic."

Could it happen again in the Netherlands?

The 14-year old boy who was paralysed in 1992 lived in the village of Streefkerk. It's a typical rural town where the church steeple stands tall in a landscape of windmills, farmland, irrigation canals and arched bridges. The boy’s family lived in a house on one side of the berm of the river Lek.

Locals remember the boy. “He delivered newspapers and some people made fun of his disability and he stopped,” recalls one man.

A local woman sitting at the town café says the parents got divorced and the family moved away. She also says that most people in the town now vaccinate their kids.

That’s also borne by evidence. Increasing numbers of Orthodox Protestants are vaccinating their children.

Henri Spaan is a 29-year-old researcher and soon to-be general practitioner who is also an Orthodox Protestant. He surveyed almost 1000 members of the Orthodox community to better understand the immunization rates and the reasons for vaccine acceptance or refusal.

Henri Spaan is a researcher who has studied orthodox Dutch Protestant communities and levels of vaccination.

Henri Spaan is a researcher who has studied orthodox Dutch Protestant communities and levels of vaccination.

He says that although people differ in vaccination choices within the church denominations, three clusters can be distinguished based on vaccination coverage. They correlate with the degree of conservatism in the church: those with a high (>85%), intermediate (50-75%) and low (<25%) vaccination coverage.

“Those who don’t vaccinate believe in a certain interpretation of the Heidelberg Catechism: what happens in the world is divine providence and humans should not interfere,” says Spaan. “Therefore, if you become sick that is coming from God and you should not prevent it, but instead put your trust in the Lord. There is also a spiritual lesson in there: if God has given you a disease you must ask yourself why.”

Spaan says that those who do vaccinate argue that the community uses other forms of prevention such as irrigation to prevent drought, or safety measures to prevent accidents. Moreover, they consider vaccination to be a gift of God. It follows therefore that vaccination is allowed and about 85% of this group has vaccinated their children. Spaan’s father was a doctor and he had his children vaccinated. Spaan and his wife have vaccinated their young daughter.

Henri Spaan and his wife have vaccinated their baby girl.

Overall, Spaan’s research showed that vaccination rates amongst Dutch Orthodox Protestants is increasing. He found that 55% of the respondents were vaccinated, in contrast to 40% of their parents - indicating a 15% increase in one generation amongst those surveyed. Sixty-five per cent of the respondents who were parents or planned to become parents said they intended to vaccinate their children.

This is a positive trend, says Spaan, but he says there will always be Orthodox Protestants who don’t vaccinate and there will always be the risk of sporadic outbreaks within those communities.

Environmental Surveillance

The Dutch public health authorities are practical about the continued risk of outbreaks. Dr. van der Avoort stresses that the Orthodox communities are “very good citizens," they simply don’t vaccinate due to deeply-held religious beliefs. So, it follows that given the high-rates of vaccination for the rest of the Netherlands, a good surveillance system rather than forced vaccination is the most pragmatic public health measure.

Since the 1992 outbreak, the Dutch have conducted environmental surveillance for polio and other viruses that can be detected in the gastrointestinal tract.

The method is straightforward. Every three weeks, RIVM contractors pull sewage samples from the sewer systems near schools with high numbers of Orthodox students enrolled. The Bible Belt is a sentinel group for the rest of the population.

Laboratory technicians examine up to 120 environmental samples in a year. Since 1992, day after day, and year after year, they’ve found no positive samples for polio. But they know they could, and that they’re looking in the right place.

It’s this kind of safeguard which means that even if polio returned to the Bible Belt, the laboratory would be ready to spot it, respond and report an outbreak to the world as needed.

“The 1992 outbreak taught everybody that as long as there is wild polio circulating, these groups in the Bible Belt can be infected. To truly end polio in the Netherlands, we must finish it everywhere in the world.”

How Europe Ended Polio

Operation MECACAR

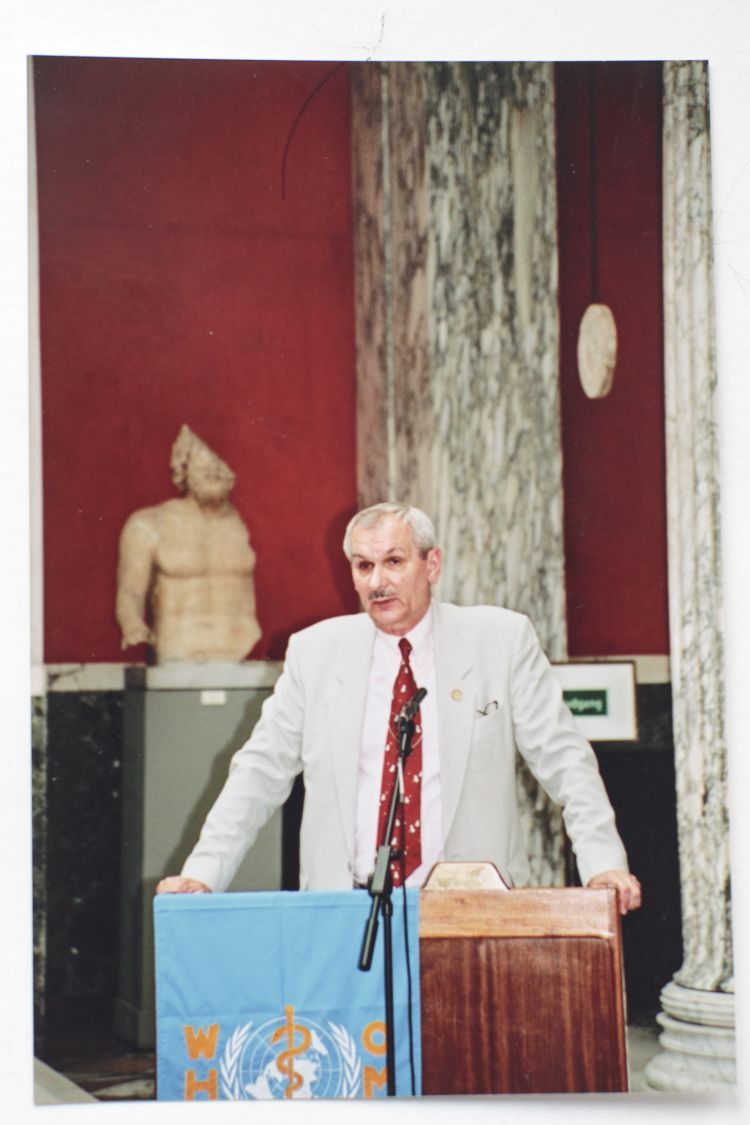

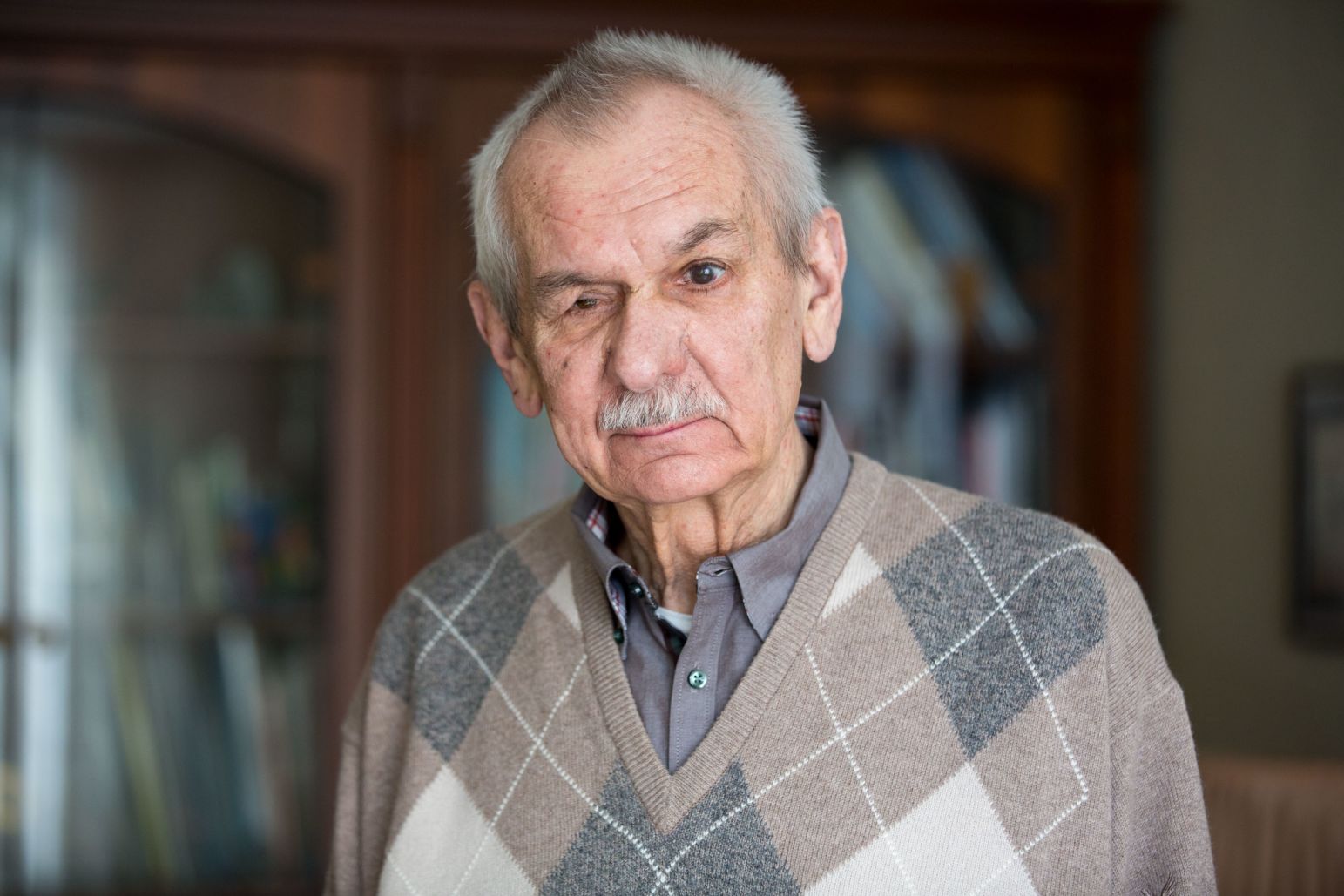

Dr. George Oblapenko had a huge task on his hands. From a small WHO office in Copenhagen, he was responsible for motivating every country in Europe to eliminate polio by the year 2000.

“I had a budget of $20,000,” remembers Oblapenko. “For that I was able to conduct two meetings. Not big ones.”

Dr. George Oblapenko led the WHO European office's effort to end polio in Europe in the 1990's.

Dr. George Oblapenko led the WHO European office's effort to end polio in Europe in the 1990's.

He took the job on 8 May 1990, at a time when WHO kept track of every long-distance phone call made by staff. A desktop computer was a big deal. Email was in its infancy.

To add complication, soon after George started, the Soviet Union began to break apart. He initially had 41 countries under his responsibility. As the Iron Curtain came down, he had a dozen more countries to plan for.

“The polio eradication plan of action I drafted in 1990 became useless in 1991."

Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan all experienced polio outbreaks in the early 1990s. The Russian Federation had a large outbreak in 1995. Turkey also had cases every year.

Stopping polio was going to be difficult.

Watch a video about George Oblapenko's effort to end polio in Europe, and continue scrolling to read more.

Learn how Dr. George Oblapenko coordinated efforts to end polio in Europe.

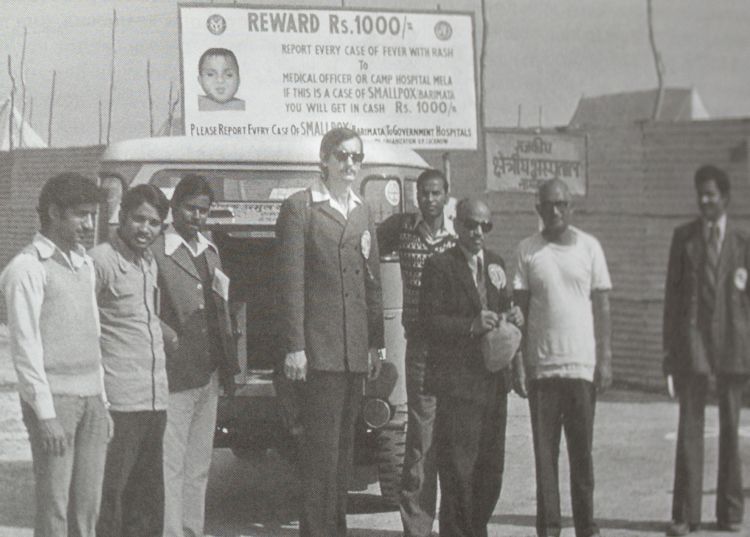

Oblapenko, like many who worked in polio eradication, had been a smallpox warrior too.

As smallpox disease was being corralled into a few remaining hotspots in 1975 Oblapenko was asked to take leave from the Pasteur Institute (in what was then called Leningrad) and travel to Bihar state in India. There, he worked with local health authorities to find smallpox cases and helped to vaccinate communities at risk. He returned again for several months the following year. Lessons from smallpox would be invaluable for polio eradication.

“I learned how important it was to coordinate as a team with people in different fields. I worked with UNICEF for example, who were not epidemiologists. We worked with the local doctors – they were also finding cases of smallpox. And we worked with the general public, including village leaders, so they knew why we were there and how they could help us.”

I

Polio knows no borders

The seeds of Oblapenko’s idea to end polio in Europe were planted at a technical meeting in Guatemala in 1991. “At the time Europe was facing up to 300 new cases of polio each year,” remembers Oblapenko. “And Dr. Olen Kew of the US Centers for Disease Control presented new findings using genetic sequencing – showing that almost all of the cases were due to importations from countries like Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan.”

The findings stayed with him – but it was three years later when Oblapenko decided to use the information to shift Europe’s polio elimination plans. He learned that polio eradication would be the theme for World Health Day on April 7 of 1995. “I was talking to my friend Dr. Rafi Aslanian – we knew one another from smallpox days – and he was in charge of polio eradication in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region.

I realised that to stop polio in my region, it had to be stopped too in territory beyond Europe’s borders.

I proposed to Rafi that we coordinate national immunization campaigns across our two regions the week of World Health Day. He agreed.”

The project needed a name. Thinking through the participating sub-regions , Operation MEditerranean, CAucasus, and Central Asian Republics – MECACAR – was born. Oblapenko started planning.

The areas of two WHO regions that took part in Operation MECACAR.

The areas of two WHO regions that took part in Operation MECACAR.

“I was shocked to realise we would need $5 million for the vaccine alone.” This was $4,980,000 more than his operations budget.

He pitched the idea to Rotary's PolioPlus Program. Rotary agreed to the funding - if the countries would agree. Oblapenko consulted countries over the course of several meetings in 1994. Finally at a meeting in Ankara , countries across both regions enthusiastically agreed to coordinate polio activities from 1995 to 1997.

“So the Rotarians were happy with this buy-in, and they signed a cheque over to UNICEF for the vaccine," says Oblapenko. I remember going to the Copenhagen office of a Mr. Kwon at the UNICEF supply division, who that very evening was calculating vaccine needs down to the last vial – he wanted to be sure it would all be transported to the right places on time.”

Operation MECACAR takes flight

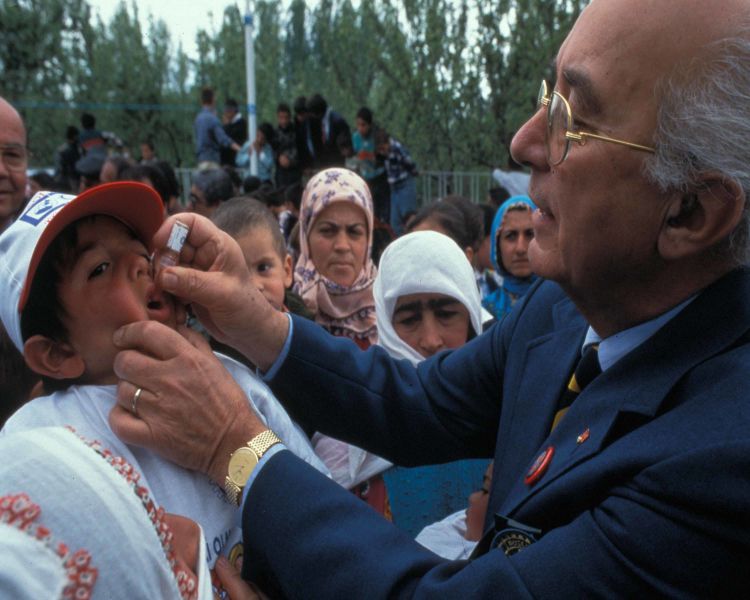

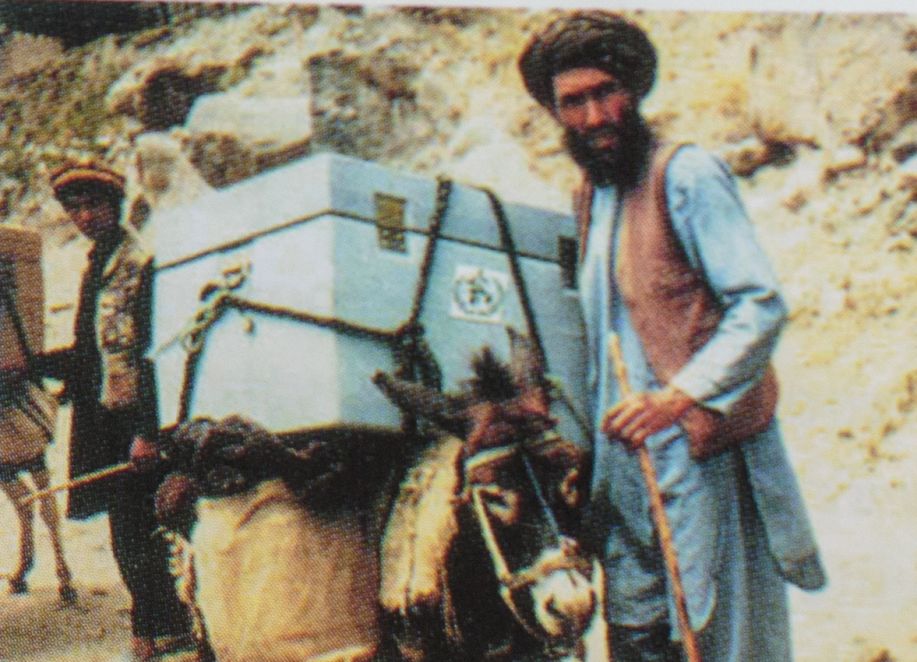

In April 1995, as Operation MECACAR was launched, Oblapenko personally travelled to Kazakhstan to monitor the vaccination campaign. In a remote mountainous area near the Chinese border he saw a man carrying a bucket of ice on horseback.

“I stopped him to ask him how he was doing. And he said: ‘I’m feeling so good, so proud, because today there are 18 countries working together to end polio forever.’ This was astonishing, as it was essentially the same speech I’d been giving to national staff during training. The messages had found their way right down to the health workers in the most remote areas."

The well-trained motivated health workforce, who knew what to do and why they were doing it, continued to be a strength of Operation MECACAR and a lesson for polio eradication.

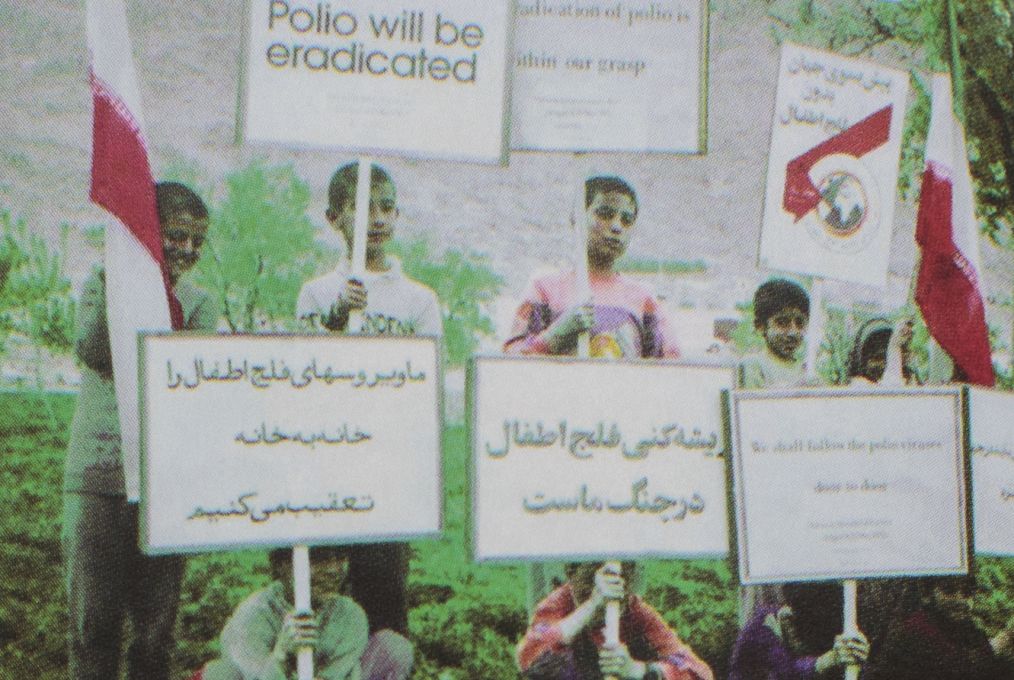

In the first year of Operation MECACAR, health workers vaccinated about 55 million children under five years of age, and about 60 million in the years that followed.

Challenges

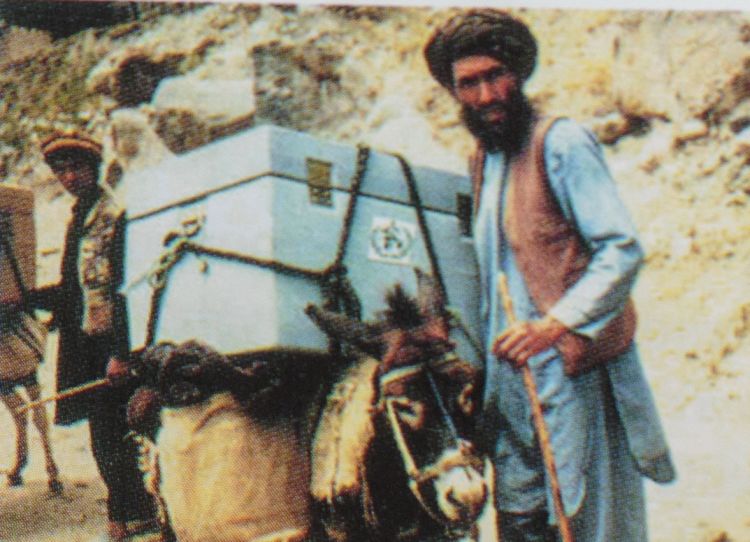

Reaching all of those children was a challenge. At the time, there was no functional cold chain. As much as Oblapenko loved meeting that Kazakh health worker with the ice bucket, he knew that couldn’t be a sustainable way for health workers to keep vaccines cold for hours and even days.

“Nobody was aware of how important the cold chain would be, because it didn’t exist. Health workers had been keeping vaccine in the health centre refrigerators. There had been no model of outreach vaccination before. We had to develop new ways to keep oral polio vaccine cold in the most remote places,” recalls Oblapenko.

With partner support, countries managed this too.

Then there was surveillance. It was uneven through the region.

“I remember Dr. DA Henderson, the former director of the WHO global smallpox eradication program, telling me:

‘We have three priorities. The first one is surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). The second one is surveillance for AFP. The third one is surveillance for AFP. This was the weakest point for many countries.”

This wasn't straightforward. “Surveillance required clinicians, epidemiologists, laboratory scientists, and government authorities to communicate closely. Acute flaccid paralysis in particular requires a strong laboratory network. ”

To help strengthen laboratories and surveillance, a Russian polio specialist named Dr. Galina Lipskaya went on leave from her laboratory and joined George’s polio team in 1997.

“The Newly Independent State countries initially had quite weak capacity,” says Dr. Lipskaya. “But with support from WHO HQ, the Rotary Foundation and the CDC, I travelled to many newly-independent states to provide training to strengthen laboratories.” The work was successful and “very soon we felt the NIS laboratories were strong and picking up the majority, if not all of the polio cases.”

Coordination across countries and regions

When Oblapenko originally planned Operation MECACAR with the countries, they agreed to exchange information freely. This was something that wasn’t easy in countries with different political systems at a fraught period in geopolitics.

Once a year, in cities including Tehran, Tashkent, Rome, Cairo and Ankara, the representatives from each of the 18 MECACAR countries came together to present progress, challenges and agree solutions, together with partners including WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, UNICEF and often USAID and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent.

At each meeting, recommendations were made to hone in on polio- whether national or sub-national polio campaigns or focussed door-to-door “mopping up” campaigns in border areas. Health workers were asked to identify children who were 'zero-dose' children rather than just tally total coverage based on target populations. Smaller groups of countries at higher-risk held their own coordination meetings to stop cross-border transmission.

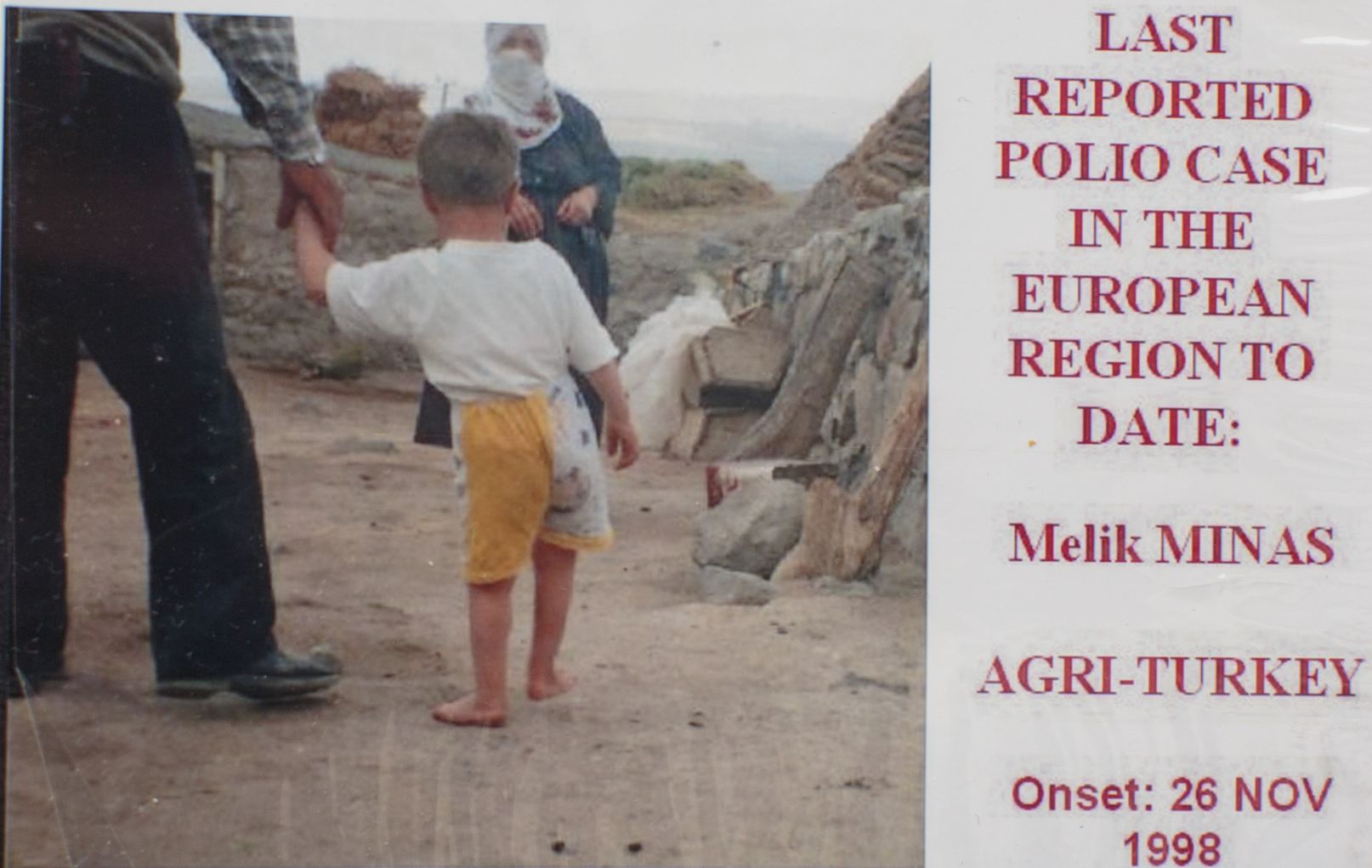

By the fifth MECACAR coordination meeting in Cairo in October 1998, only one European country, Turkey, was reporting cases.

On 26 November 1998, a young boy called Melik Minas, living in south-eastern Turkey, was diagnosed with polio. He would become the last case in Europe. The WHO European region was certified polio-free on 21 June 2002.

A photo of Melik Minas from Oblapenko's photo album.

A photo of Melik Minas from Oblapenko's photo album.

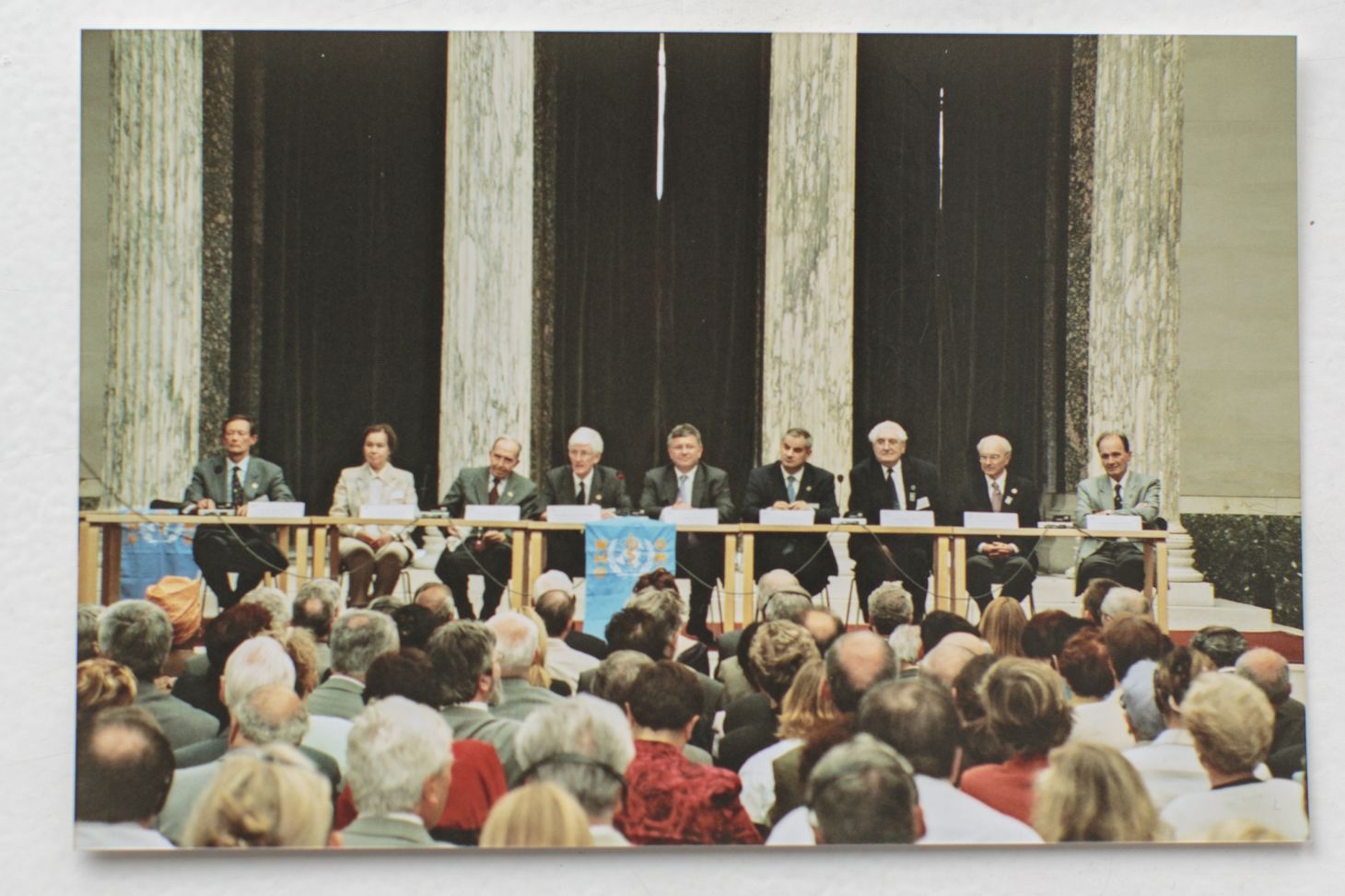

The WHO European region's polio-free certification meeting. From George Oblapenko's archives.

The WHO European region's polio-free certification meeting. From George Oblapenko's archives.

“Partnership!” Oblapenko told the certification meeting in Copenhagen. “It would be difficult to over-estimate the role of partnership in this anti-polio coalition. Trust, respect, openness and readiness to be coordinated are the main characters of this excellent partnership."

“We are all different,” he continued, “that is why we are strong. No one of us is as strong as all of us. I am sure that it is only thanks to this strong and effective partnership we have been able to clean poliovirus out of Europe.”

Oblapenko is now retired in St. Petersburg where he lives with his wife Mary. Their home contains a substantial library filled with classic volumes about immunization. The Smallpox “red book.” Vaccines. He keeps many archives from Operation MECACAR including the reports and photo albums.

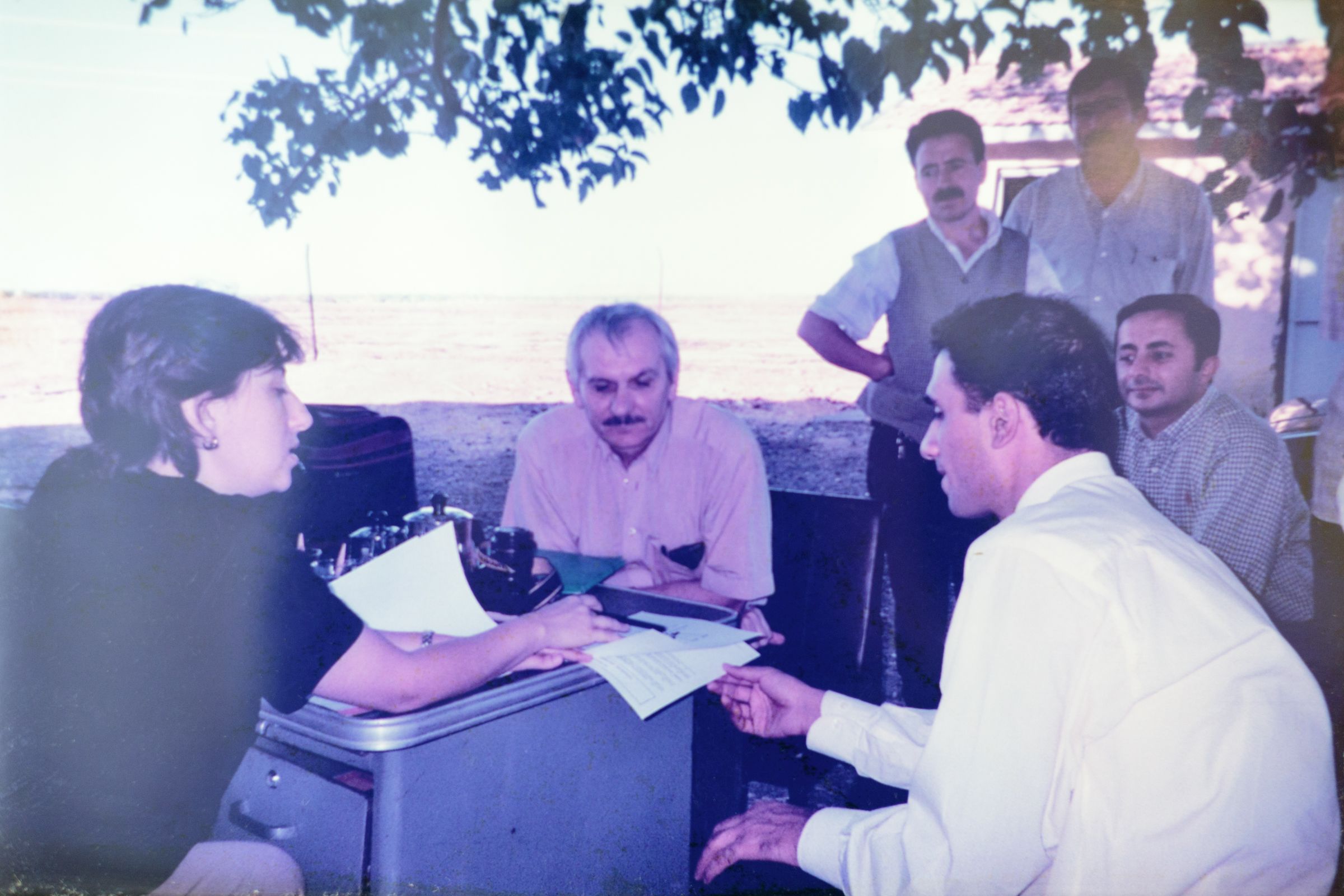

There are many photographs on the wall – one of him in Turkey sitting with colleagues in a field, planning an end to polio in the country.

Advanced glaucoma has robbed George Oblapenko of his vision. But when asked about the photographs, he could describe every one of them.

Celebrity Success

Amitabh Bachchan

Helps End Polio in India

It was 2002, and it was a bad year for polio eradication in India.

In 2001, the country recorded 268 polio cases. But in 2002 case counts were growing daily – they would hit 1556 by year’s end. In some areas, too many parents were rejecting the polio vaccine on campaign days. UNICEF was working to address the problem.

“UNICEF was under a lot of pressure,” remembers Michael Galway, then newly-hired to mobilize Indians to promote and demand polio vaccine. “A lot of people were really upset with us. In meetings, we were heavily criticised by very senior people.”

“I remember after one particularly raucous meeting, the UNICEF country representative came to my office and said, ‘I don’t care what you do, but do something!’”

This was the beginning of one of UNICEF’s most successful celebrity collaborations.

Watch the video below to learn how Amitabh Bachchan, king of Indian cinema, helped to end polio - and scroll to read more.

See how India's king of cinema helped to end an ancient disease.

Bringing on Amitabh Bachchan

“I felt we needed a really big statement,” says Galway. “I wanted a mass media campaign, together with huge visibility in marketplaces and other community hubs.”

Mr. Amitabh Bachchan with Piyush Pandey. Photo courtesy of P. Pandey.

Galway asked major advertising firms to bid for the job. Ogilvy was selected. “UNICEF and the Indian Ministry of Health approached me,” remembers Piyush Pandey, the creative director at Ogilvy South Asia. “They wanted me to contact Mr. Bachchan, as I knew him.”

“Amitabh Bachchan never says no to any public service calls,” continues Pandey. “

Mr. Bachchan says, given the burden of polio to India, it was clear he should contribute.

“I think it comes very naturally for anyone that if they want to do something for the nation, to make life better, on an issue that is plaguing the country – you want to do this. UNICEF asked me to take part and I happily agreed.”

A Bold Campaign

Piyush Pandey at Ogilvy developed a concept. “Work on polio had been going on for a long time and the messages weren’t breaking through,” says Pandey. “We needed a new approach, and I wanted to get the best out of Mr. Bachchan.”

“I said to him ‘you’re known for your roles as the angry young man. Now you can play the angry old man for me.”

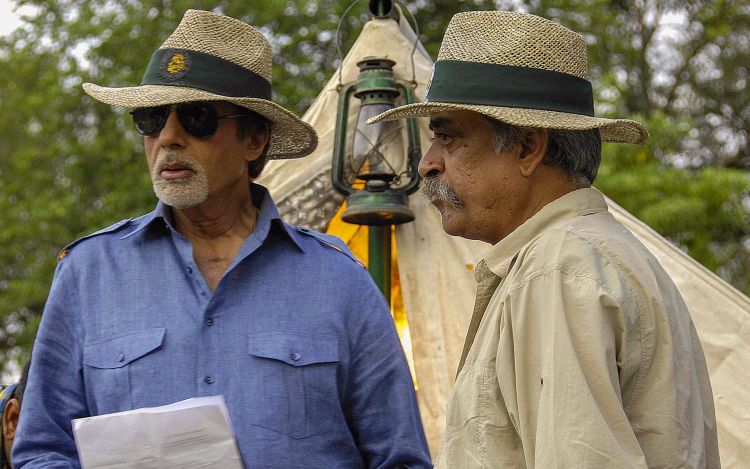

Mr. Bachchan’s "angry young man" was an established character type for him in the early 1970s, when films including Zanjeer (Shackles) and Deewar (The Wall) portrayed a rebellious man, fighting corruption and authority.

“They felt that maybe I should be playing characters I’d played in some of my films, where I get a little upset,” says Bachchan.

Piyush Pandey brought the concept to Michael Galway and the Ministry of Health.

Amitabh Bachchan in "Zanjeer", a film that established his "angry young man" character.

The idea: An angry Amitabh Bachchan, slams his fist down in anger, and chastises Indians for not taking their children the short distance to the polio vaccine campaign booth.

“I remember feeling sick reading that script,” says Galway. “I couldn’t believe we were meant to go out and scold the country. You weren’t supposed to chide people. You were supposed to bring them around by appealing to their values. I was nauseous about it.”

“Piyush says ‘don’t worry. It will work because it’s Amitabh.’”

So with a deep breath, UNICEF and the Ministry of Health put their faith in Ogilvy and Amitabh Bachchan. From there, they went full speed ahead.

Launch Day

The first broadcast public service announcement (PSA) coincided with a huge polio campaign. Galway was out in the field monitoring the campaign, “feeling all testy as UNICEF was being beaten up so much.”

“The World Health Organization State Coordinator called me. I was ready to be beat up some more.”

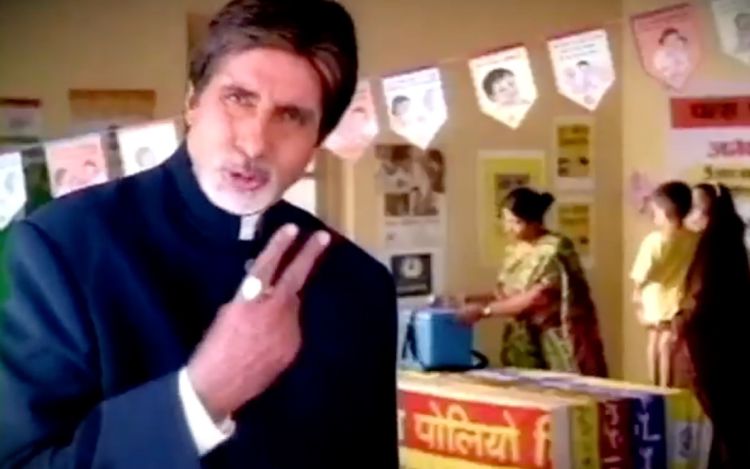

Amitabh Bachchan, in an early polio campaign, scolding the country for not attending the polio vaccination booths.

But he said: “Michael, it’s a miracle! People are flooding out to the booths because of Amitabh!”

The PSA features Mr. Bachchan in front of an empty polio booth. He’s angry. “Shame on us!”, he scolds. “So few people at the polio booth! Two drops can give your child a life! And for that, you can’t even walk four steps? Come on!”

“He was like a senior member of the family who has license to tell you what to do – he seems angry, but he’s telling you out of affection,” says Piyush Pandey.

“People weren’t sure if he was acting, or he really was mad at them. But either way, he was so incredible,” remembers Michael Galway. “We got fantastic feedback.”

Do boon zingdagi ke!

Polio vaccine coverage increased, and the Amitabh Bachchan campaign changed tone. “It became an “I’m really proud of you” message, says Piyush Pandey. “Like if you scold someone you care about for smoking, and they actually quit, and you tell them you feel so proud of them.”

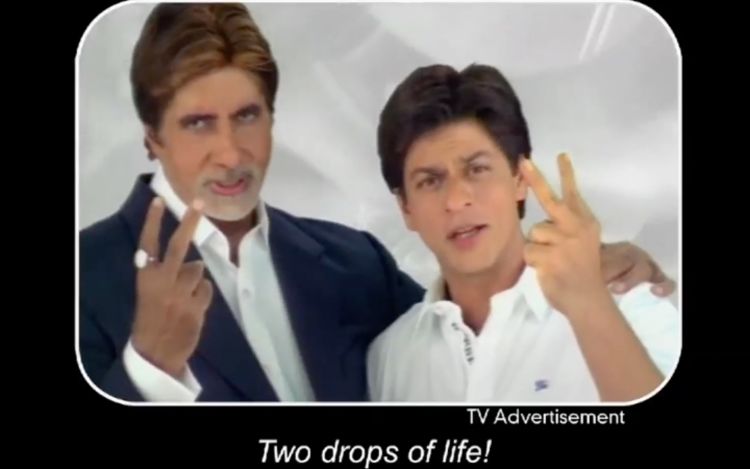

Bachchan’s mantra, Do boon zingdagi ke!, would become known across the country – from remote villages to the biggest cities. When UNICEF staff travelled to rural communities and said “do boon”- “two drops” – children would repeat back “zingdagi ke!”

Two drops of life. A simple, memorable tagline.

As the years went on, the campaign tone continued to shift. The message in later years featured a “we’re all rising up together” feel – like a national movement.

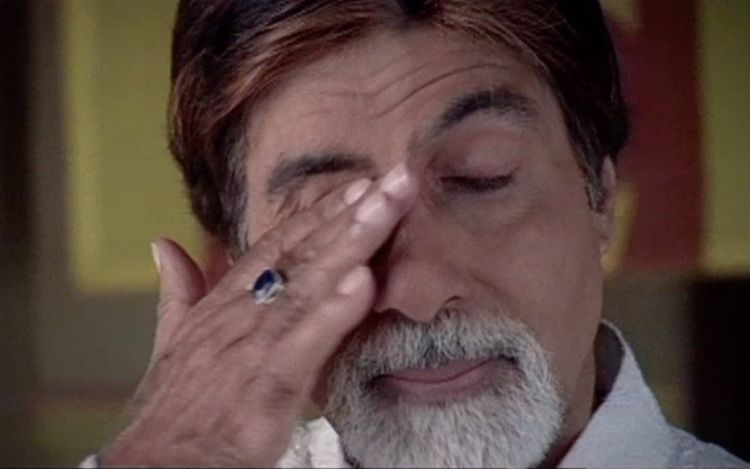

One PSA features Bachchan standing at an empty polio booth in the dark in the pouring rain. No one is coming. All of a sudden, an army of parents arrives, each person clutching an umbrella in one hand, a baby in the arm, a child on the other hand. The music swells, and Bachchan wipes away tears. You don’t need to speak Hindi to understand the message.

More celebrities join

Amitabh Bachchan’s involvement triggered even more celebrity participation. His wife, renowned actress Jaya Bhaduri Bachchan, and daughter-in-law, Aishwarya Rai, joined. There were cricketers and more actors, including megastar Shah Rukh Khan – all enjoining India to receive “two drops of life!”

Amitabh Bachchan says the fact more celebrities joined only helped to reinforce the message.

“It’s not just me saying it. There were several more glamorous celebrities involved. The entire fraternity is keen, is involved and interested and wanting to you to believe that do boon zingdagi ke is going to be helpful for you. For them to come forward and say this, it was important.”

Real time and real money

Amitabh Bachchan has continued his commitment to polio for years, from 2001 through to today. He’s still advocating for continued vigilance against polio, for routine immunization, and diseases including Hepatitis B. He does all of the work for free. However, producing video and distributing campaigns across India costs a lot of money.

“UNICEF and the Ministry of Health were relentless in finding the funds to keep the campaign going,” says Piyush Pandey. “I’ve seen many situations when people do this work, the money runs out, and it just disappears. They really found the resources to make it happen, for years. And we just kept at it.”

In 2011, India identified a little girl in West Bengal who would become the last child with polio in all of India, and all of the South-east Asian Region of WHO. Three years later, the region was certified polio-free.

Many give Amitabh Bachchan credit for helping to end polio in India.

“The campaign is now legendary in any social service space, and we’re very proud of that," says Piyush Pandey. "In 2014 when India was certified polio-free, we talked and laughed together like little kids, we were so excited about what we’d achieved. And then I cried because of what we’d achieved.”

Amitabh Bachchan says he's proud India ended polio. But until polio transmission ends everywhere, he also stresses caution:

"There is always going to be a warning – polio may be eradicated today and come back tomorrow. Neighbouring countries could have polio. The virus can travel from there. There is always a danger of it reappearing. So we have to watch ourselves."

Acknowledgements

Our World United to End Polio is the result of a collaboration of the United Nations Foundation, with partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

Christine McNab, an independent multimedia producer specialising in global health and development, produced the series. The project was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

OVERALL PRODUCTION

Executive producer, photographer, writer, narrator: Christine McNab

Video editing: Kathryn Dickson, OnFireFilms.tv

Graphic design and animation: Ron Sloan

Music, Re-recording Mixer: Michelle Irving, Soleil Sound

Colour Correction: Mario Baptista

The team in front of the Pichanaki shop where Luis works.

The team in front of the Pichanaki shop where Luis works.

Luis: The First Last Case

Camera and sound: Alexander Houghton

Location producer: Andrea Zarate

Translator/Fixer: Da Sánchez Suárez

Interpretor: Enrique L. Sánchez

Additional Photos: 1991 photos from Pichanaki courtesy of PAHO

- Additional historic photos courtesy of Gustavo Gross of Rotary International

With special thanks to: Peru's Ministry of Health, Dr. Roger Zapata, Luis Fermin Tenorio Cortez, Sr. Gustavo Gross and family, Joaquin Delgado, Dr. Jorge Medrano, Dr. Mariam Strull.

An Outbreak in the Netherlands

Camera and sound: Esther Verkaik

With special thanks to: RIVM the Netherlands, Dr. Erwin Duizer and his team, Dr. Harrie van der Avoort, Dr. Henri Spaan and family.

George and Mary Oblapenko at their St. Petersburg home.

George and Mary Oblapenko at their St. Petersburg home.

How Europe Ended Polio

Camera and Sound: Daria Ustenko

Production Manager: Anzhela Fedoseeva, Andy Fiord Production

Additional Photos: with thanks to Rotary International

With special thanks to: Dr. George and Dr. Mary Oblapenko.

Celebrity Success in India

Camera and Sound: Ravi Lekhi

Interviewer: Geetanjali Master, UNICEF India

With special thanks to: Amitabh Bachchan, Piyush Pandey, Michael Galway, UNICEF India.