No Step too Steep

India, the USA and Pakistan

Our World United to End Polio profiles individuals from around the globe who have committed their expertise, time and passion to the world-wide effort to eradicate polio. It's a journey that began in the Americas in the 1980s, has crossed every continent, and is now focussed on a handful of countries still facing polio outbreaks.

In this immersive series, engage with photos, videos, animation and stories about people who have given everything to end a disease.

Meet Martha Dodray, an Indian health worker who has forged trust with the families who live in one of India's harshest climates.

Learn how Dr. Cara Burns tracks polio from all over the world, and stays ahead of a virus that has taken some surprising twists.

Meet Aziz Memon, a Rotarian who works every day to take the politics out of polio eradication.

To experience these stories, simply scroll down.

To skip to a new story, click on a title in the menu bar.

Stopping Polio Beyond

the End of the Road

Lessons from India's Kosi River Basin

When Martha Dodray spent her days immunizing children against polio, she looked forward to waking up in the morning. "I was excited about the job. I couldn't sleep the night before."

Martha crosses a river on a bamboo bridge in India's Kosi River Basin area.

Martha crosses a river on a bamboo bridge in India's Kosi River Basin area.

Not everyone would share Dodray’s enthusiasm, as her job involved reaching communities in one of the most remote and challenging areas of India’s polio eradication program.

“Sometimes I’d have to walk by foot or travel by boat and reach these areas, and sometimes I’d have to wade through water to reach my destination. It was quite challenging to face the elements,” Dodray remembers.

Watch the video below to see how Martha Dodray served hard-to-reach communities in an effort to end polio in India. Continue scrolling to learn more about stopping polio in India's Kosi River Basin area.

See how Martha Dodray managed to reach children in one of India's most challenging areas.

See how Martha Dodray managed to reach children in one of India's most challenging areas.

Martha Dodray is a government health worker. Her station is in Darbhanga, a district in India’s Kosi River Basin area and one of the last bastions of polio in India.

"Darbhanga has all the diseases and all the difficulties,” says Dr. Rajendra Kumar Singh, who supervises the World Health Organization’s work in Darbhanga, as part of the WHO National Polio Surveillance Project (known widely as NPSP). Child malnutrition is a problem. So is cholera – a condition linked to challenges with water and sanitation. So was the presence of poliovirus.

The vast, flat nature of the terrain in the Kosi River Basin is hard to fathom. In the dry season, the basin stretches in endless dusty swathes as far as the eye can see. Intermittent clumps of trees shelter villages of a few dozen people. Hindu temples mark the high points, which stand no more than 40 metres above sea level.

About three hundred kilometres away loom the Himalaya of Nepal. Each spring, in a startling show of watery force, the snowmelt races down the mountains towards the Kosi River Basin.

The river paths can change each year, but the result is the same: the dry basin transforms into an ocean several metres deep; with racing currents that can sweep boats and people away.

But the dry season was even more difficult. When the waters recede, they reveal fertile soil. People descend from the villages and spread across the basin to claim a plot of land. Families settle for months at a time, living in small temporary huts. These can be kilometres from the nearest road. Every year, the huts are washed away by the floods. Every year families rebuild, often in new places. These temporary settlements are called ‘basas.’

Families spend the dry season tending to their crops, a crucial livelihood for people in the Kosi Basin area.

Families spend the dry season tending to their crops, a crucial livelihood for people in the Kosi Basin area.

“In Kosi Basin there is no organised structure of where people will be living,” explains Dr. Sunil Bahl, of WHO. “In these periods it was a huge challenge to reach every child with polio vaccine. We were missing 10 to 20 % of children in the area."

Dr Sunil Bahl and the WHO-NPSP team worked with the Ministry of Health and partners to map a new strategy for the Kosi River Basin area.

Dr Sunil Bahl and the WHO-NPSP team worked with the Ministry of Health and partners to map a new strategy for the Kosi River Basin area.

Health workers were trying, but it was hard to monitor the quality of their work. There aren’t many roads into the Kosi River Basin area. There are no guesthouses or hotels. So typically, the polio surveillance medical officers (called SMOs) would base themselves at the nearest town. They would wake early to travel for several hours to monitor polio campaigns, and then travel several hours back on the same day.

“We would travel sometimes for 12 hours in one day – by motorcycle, boat, on foot, and could then only spend a few hours onsite,” recalls Dr. Bahl. This made it impossible to connect with the health workers and the communities and to plan polio campaigns properly.”

The Kosi River Basin area was a sanctuary for poliovirus at a time when India was working hard to eliminate polio in the country.

We had to come up with a new strategy. Fast.

“We had to be systematic,” explains Dr. Bahl.

He and the team divided the area into grids based on the river patterns. They set up new offices in larger villages and equipped them with field necessities: generators to run fans and charge mobile phones, cooking facilities, a mattress and mosquito net, clean drinking water and latrines. This way, SMOs could spend several days in the area. They could meet with village leaders, form relationships with the health workers, and draw up ‘microplans’ that included the thousands of temporary communities.

Children in Tilkeshwar village.

“This new strategy was a game-changer.”

They also established several dozen ‘stay points’ in villages – locations that were just one or two hours – rather than twelve hours –from the new village offices. These may have been as basic as a sleeping mat at the temple, but they allowed SMOs and health workers to sleep in the areas where they needed to vaccinate children, wake the next morning and get back to work rather than lose time traveling.

A woman waits to have a baby immunized.

Dr. Rajendra Kumar Singh, the SMO in Darbhanga district, remembers the days very well.

“To vaccinate the people, we had to be one of them. We had to form bonds of trust with the communities. When we stayed in the communities, we could do that.”

Dr. Rajendra Kumar Singh, a surveillance medical officer in the Kosi River Basin area.

Dr. Rajendra Kumar Singh, a surveillance medical officer in the Kosi River Basin area.

“I learned quickly that the community would really embrace you,” says Singh. “I learned not to be afraid to ask for things, including to ask for food. People were always generous.”

Children in Tilkeshwar village.

Children in Tilkeshwar village.

A woman waits to have a baby immunized.

A woman waits to have a baby immunized.

The priest at the temple in Tilkeshwar village.

The priest at the temple in Tilkeshwar village.

Martha Dodray, the health worker who was used to walking for hours just to vaccinate a few children, also remembers the change in the community. “We got to know people well. In the beginning they would sometimes reject the vaccine, but I built a good relationship with the community, and they accepted it. This was how we could end polio.”

With the new plan of village offices and stay points, the numbers of children vaccinated grew exponentially. “Within a few months we had accelerated from vaccinating children in hundreds of field huts, to reaching 250,000 of them," remembers Sunil Bahl.

"The numbers of missed children were reduced to under two percent. It was an incredible leap.”

The team used data to adjust their plans. When settlements moved, the teams moved with them. Within two years, the data told them that there was no more polio in the Kosi River Basin, or anywhere in India. The last polio case in the country was identified in West Bengal on January 13, 2011.

The Government of India was instrumental in the success of the Kosi River Basin operational plan and ultimately the eradication of polio in the country.

The government provided strong leadership, spent up to $300 million a year, and equipped tens of thousands of health workers and community mobilizers. Partners including Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation worked closely with government and WHO-NPSP.

A government health worker offers maternal checks together with vaccine during health sessions.

A government health worker offers maternal checks together with vaccine during health sessions.

Today, the groundwork laid in the Kosi River Basin has opened the door for improved health for all children.

In addition to continuing to protect children against polio, intense microplanning helps to deliver more vaccines, such as measles-rubella, pentavalent and pneumococcal vaccines, and fractional doses of inactivated polio vaccine.

WHO-NPSP is using their network to conduct surveillance for several vaccine-preventable diseases including measles, pertussis, diphtheria as well as visceral leishmaniasis and lymphatic filariasis.

Dr. Rajendra Kumar Singh sums up how his polio experience in the Kosi River Basin has informed the surveillance work he leads in Darbhanga today.

Everything I know, I learned from polio eradication.

Empowering Countries

A Global Polio Laboratory Network

What is a polio case?

When the polio eradication effort began in the 1980s, it was a question with more than one answer.

"In the early days in Peru we didn’t wait for laboratory results,” says Peter Carrasco, a polio eradicator who worked with the Pan American Health Organization's team of polio eradicators.

“Our job was to break the chains of transmission as fast as possible. If it looked and smelled like polio, we started a mop-up vaccination campaign within a week.”

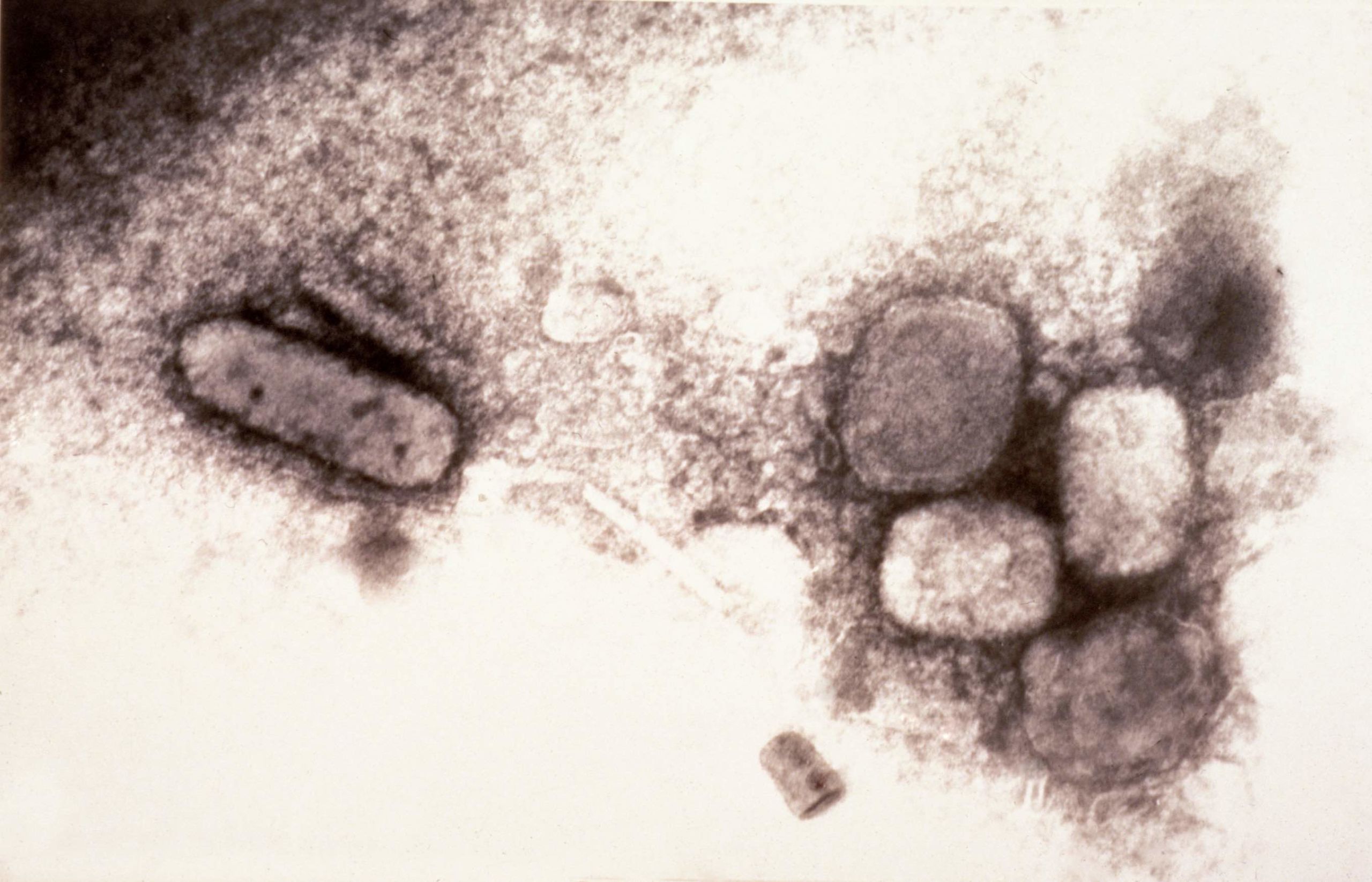

Anyone with smallpox developed a rash. But only one in 200 people infected with polio become paralysed. The poliovirus can otherwise circulate silently for long periods of time.

Polio diagnosis in the early days depended on a physical examination in a doctor's clinic. This wasn't reliable, as other diseases could cause polio-like paralysis. In wealthier countries, a polio case would be examined by a panel of experts.

Dr. Ciro de Quadros, the legendary Brazilian polio coordinator for the Americas, wanted polio to be identified in a laboratory.

“Ciro didn’t want neurologists to be debating whether a child had polio,” remembers the CDC’s Dr. Mark Pallansch, who helped to develop the global polio laboratory network. “He felt we needed to isolate a poliovirus to really demonstrate the presence of polio.”

The idea seems obvious today. But at the time, it was revolutionary. It posed several problems. How to standardize the laboratory identification of polio in every country in the world? What kind of sample could be collected from children in the field, and sent safely back to a laboratory for analysis?

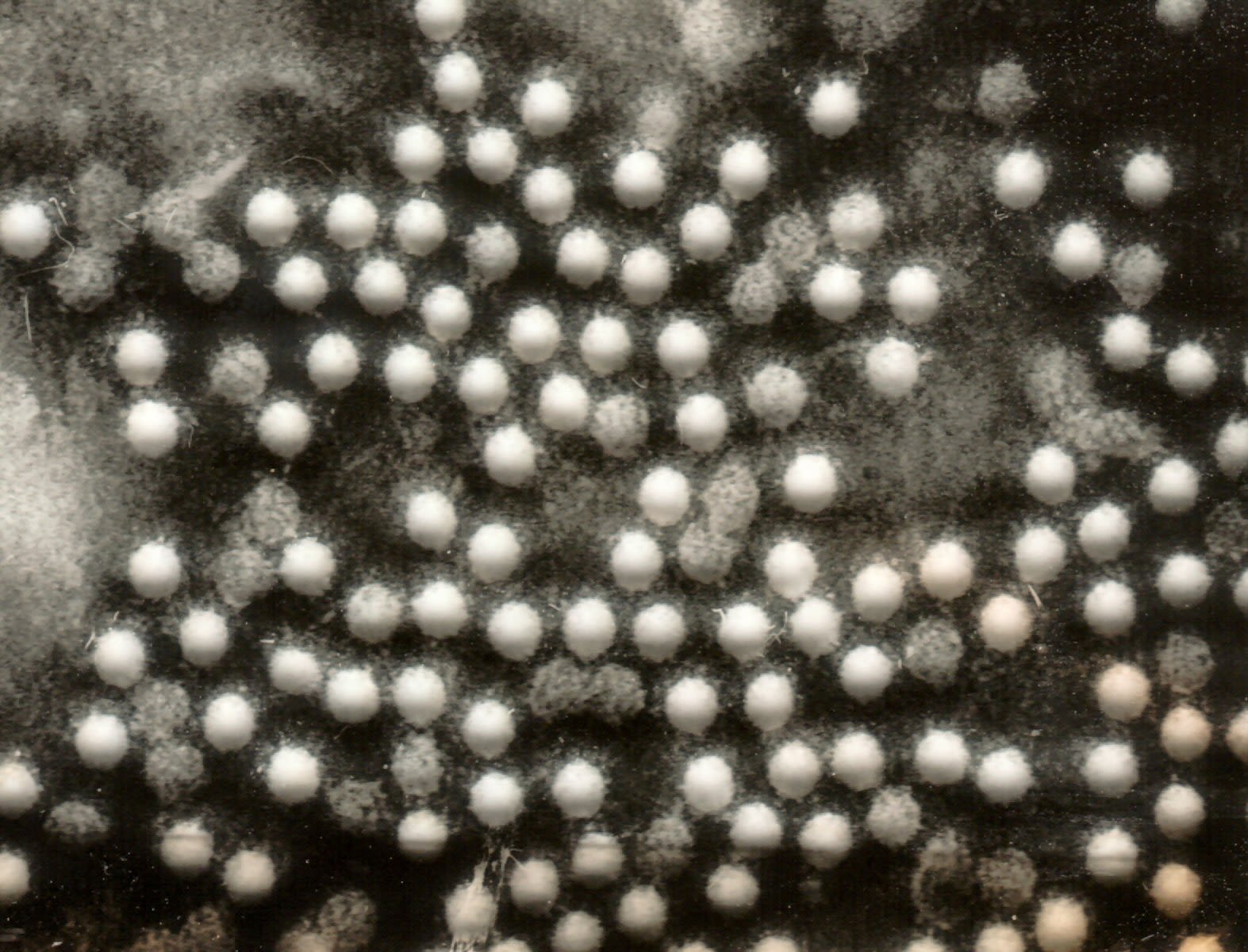

It’s not a dinner table conversation, but over time, the story of polio eradication would be told through laboratory results from stool samples.

For years, two stool samples have been collected from every child suspected to have polio, no matter where they live, and sent for analysis in a national laboratory. And each of those laboratories have the same level of training and same equipment.

Country capacity

In 1989 Mark Pallansch and CDC scientist Olen Kew travelled to Geneva to create a global plan of action for laboratory networks. A key principle was for the network to build standard methodologies in countries around the globe.

Mark Pallansch and Olen Kew of the CDC. Photo courtesy of M. Pallansch.

Mark Pallansch and Olen Kew of the CDC. Photo courtesy of M. Pallansch.

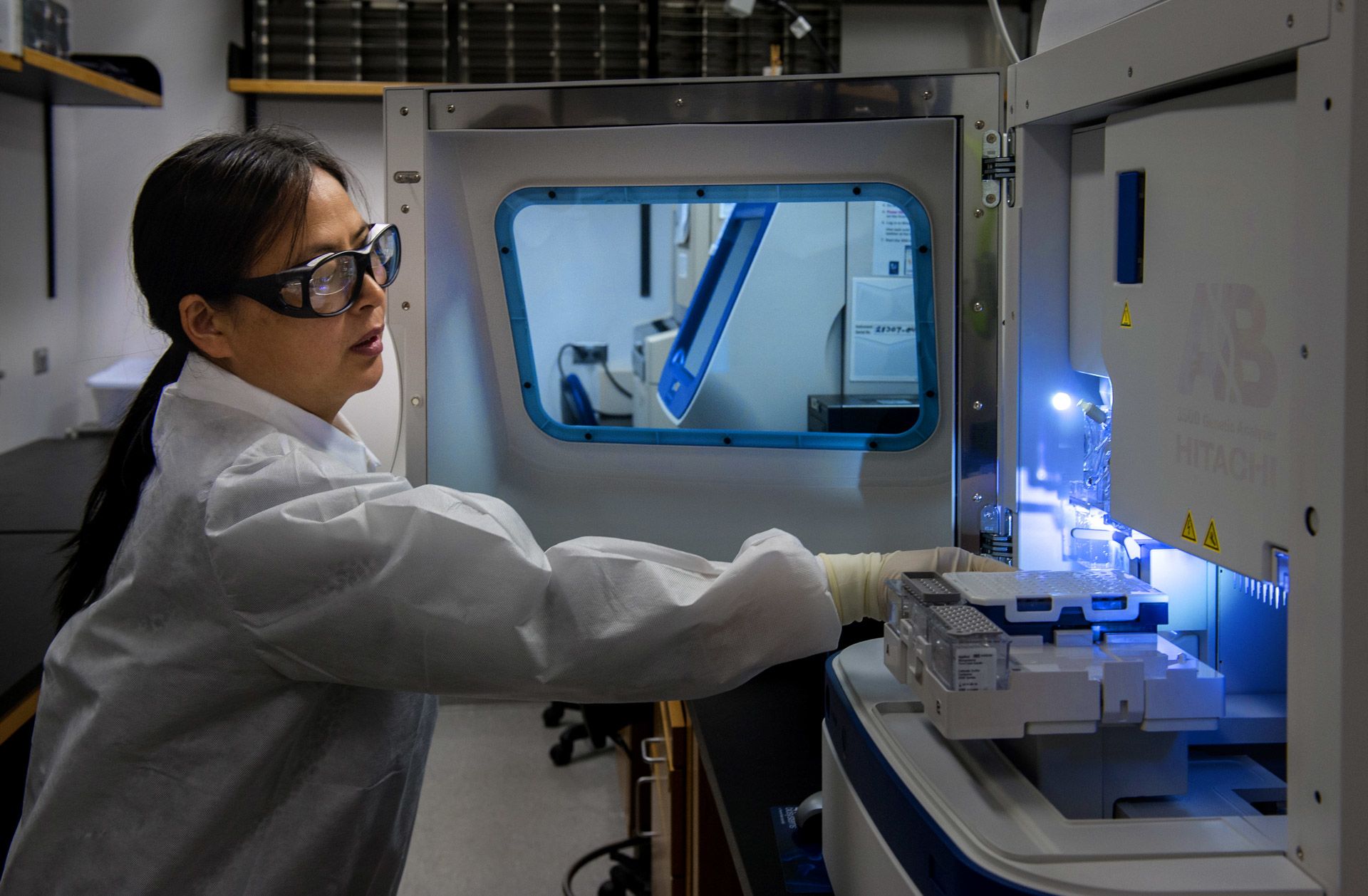

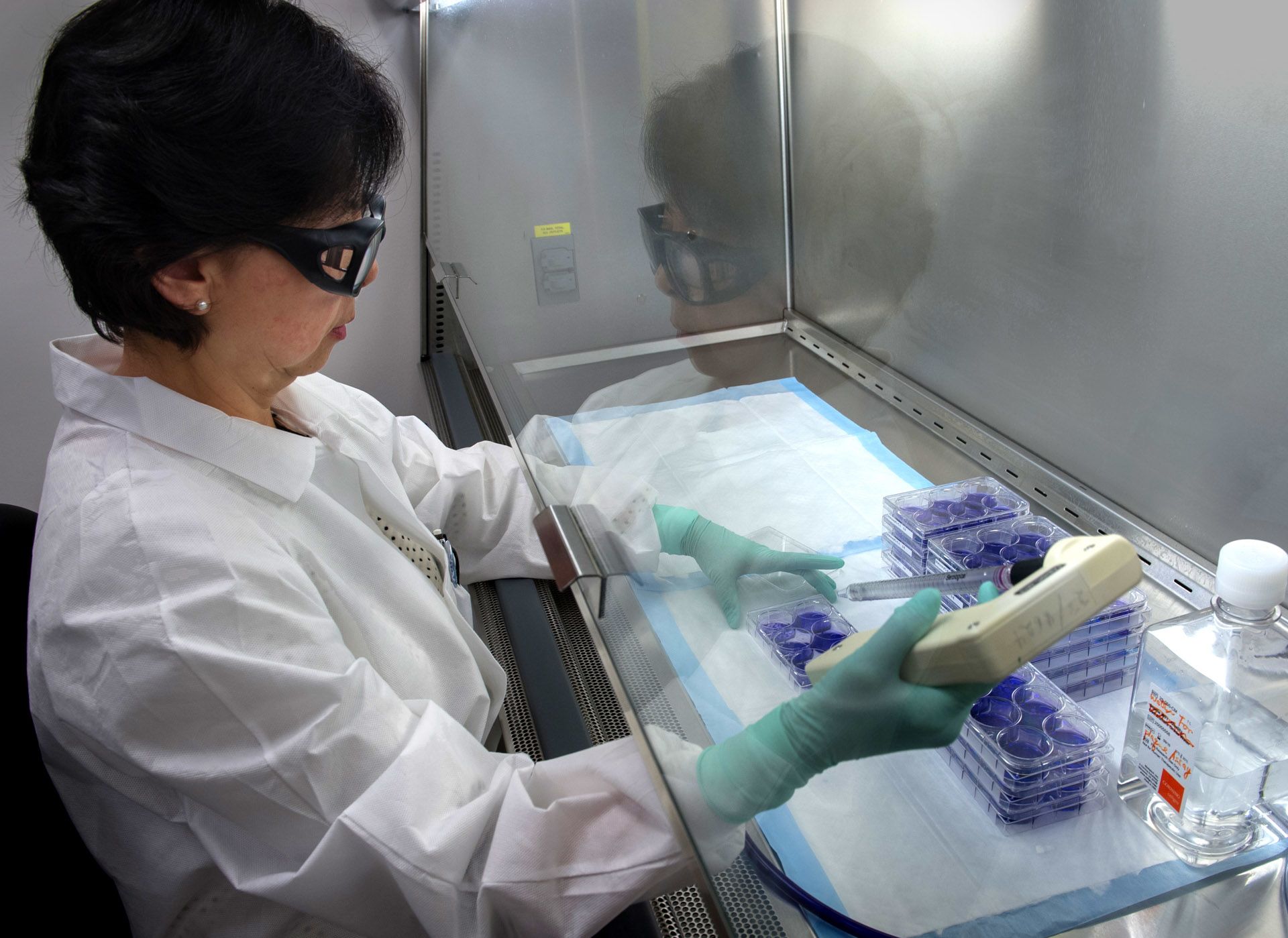

“Core capacities to isolate poliovirus in cell cultures would be built in as many countries as possible,” Pallansch explains. “There would be regional laboratories that could differentiate between wild polio and vaccine viruses. And finally, specialized laboratories that could conduct more sophisticated molecular epidemiology, including genetic sequencing.”

The CDC worked closely with the WHO and other well-resourced laboratories to train and equip national staff to the same standard.

“The target was the same for every country, whether it was Cameroon or Cambodia. If it didn’t work everywhere, the system simply didn’t work.”

Dr. Cara Burns explains how laboratory technologies had to work in every country condition.

Dr. Cara Burns explains how laboratory technologies had to work in every country condition.

The network in the Americas was strengthened to the point where polio – and its absence – could be demonstrated in every country, leading to the certification of a polio-free Americas in 1994.

By 1997 there were about 60 laboratories in the polio laboratory network, which was testing around 50,000 stool samples every year.

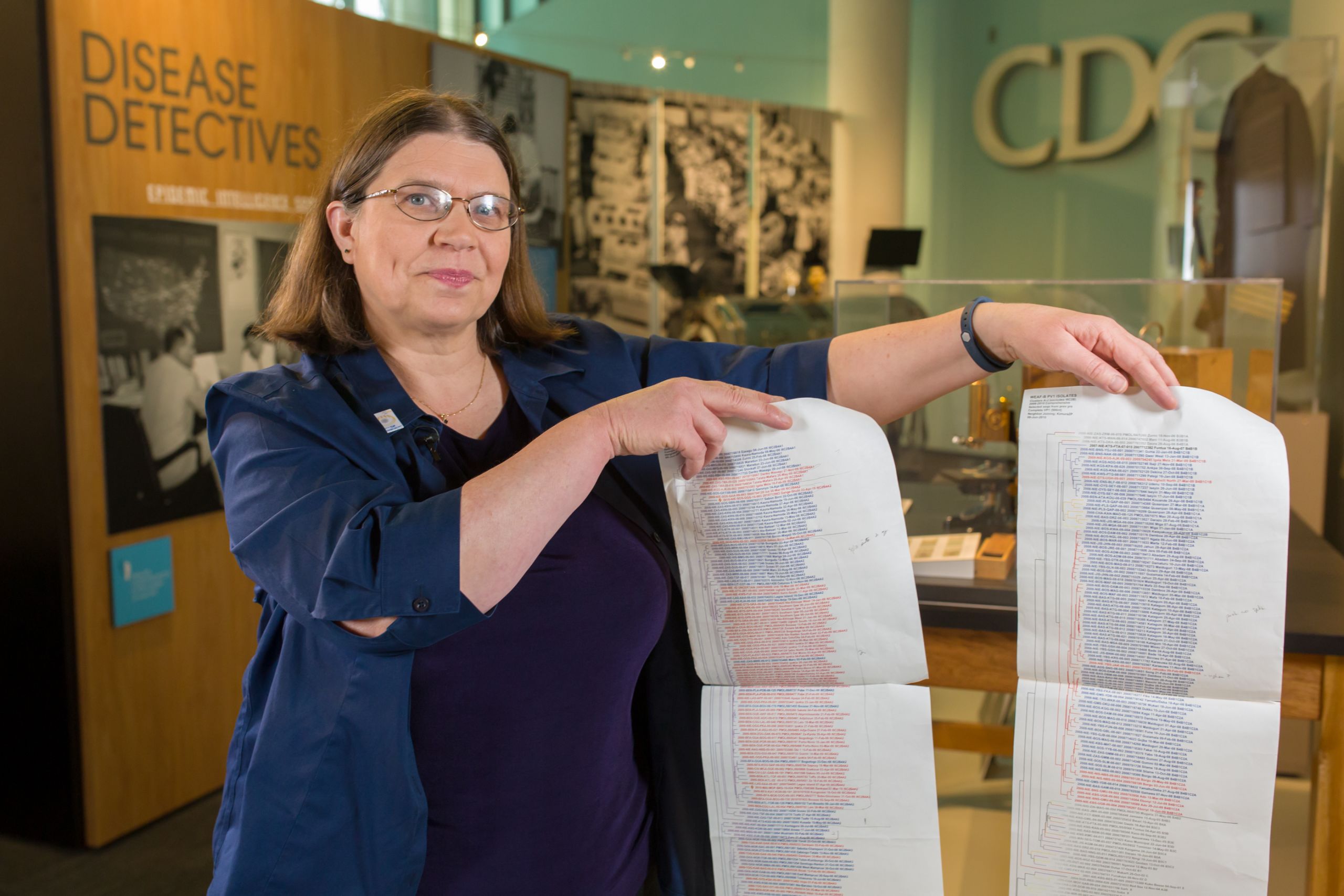

Dr. Cara Burns, now head of the CDC's polio laboratory.

Dr. Cara Burns, now head of the CDC's polio laboratory.

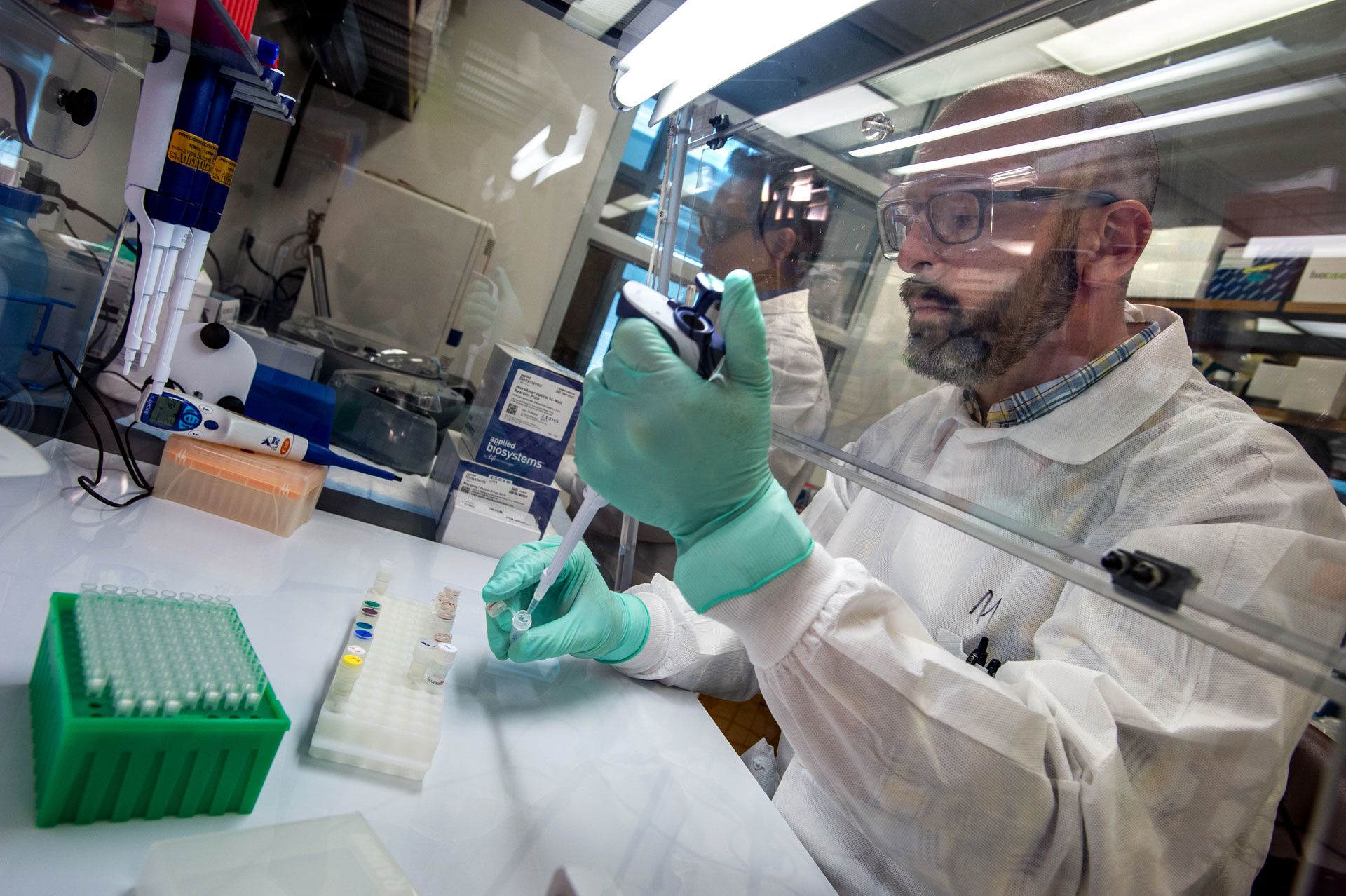

Dr. Cara Burns, now the head of the CDC polio surveillance laboratory, joined the team in 1998.

The laboratory was conducting more genetic sequencing – allowing specialists to map the way the virus was spreading and changing. They could tell for example, when a virus from southern India traveled to Turkey based on the genetic characteristics.

“Poliovirus changes about 1% of its genetic make-up every year. This is enough for us to be able to track the virus using the tools of molecular epidemiology," says Cara Burns.

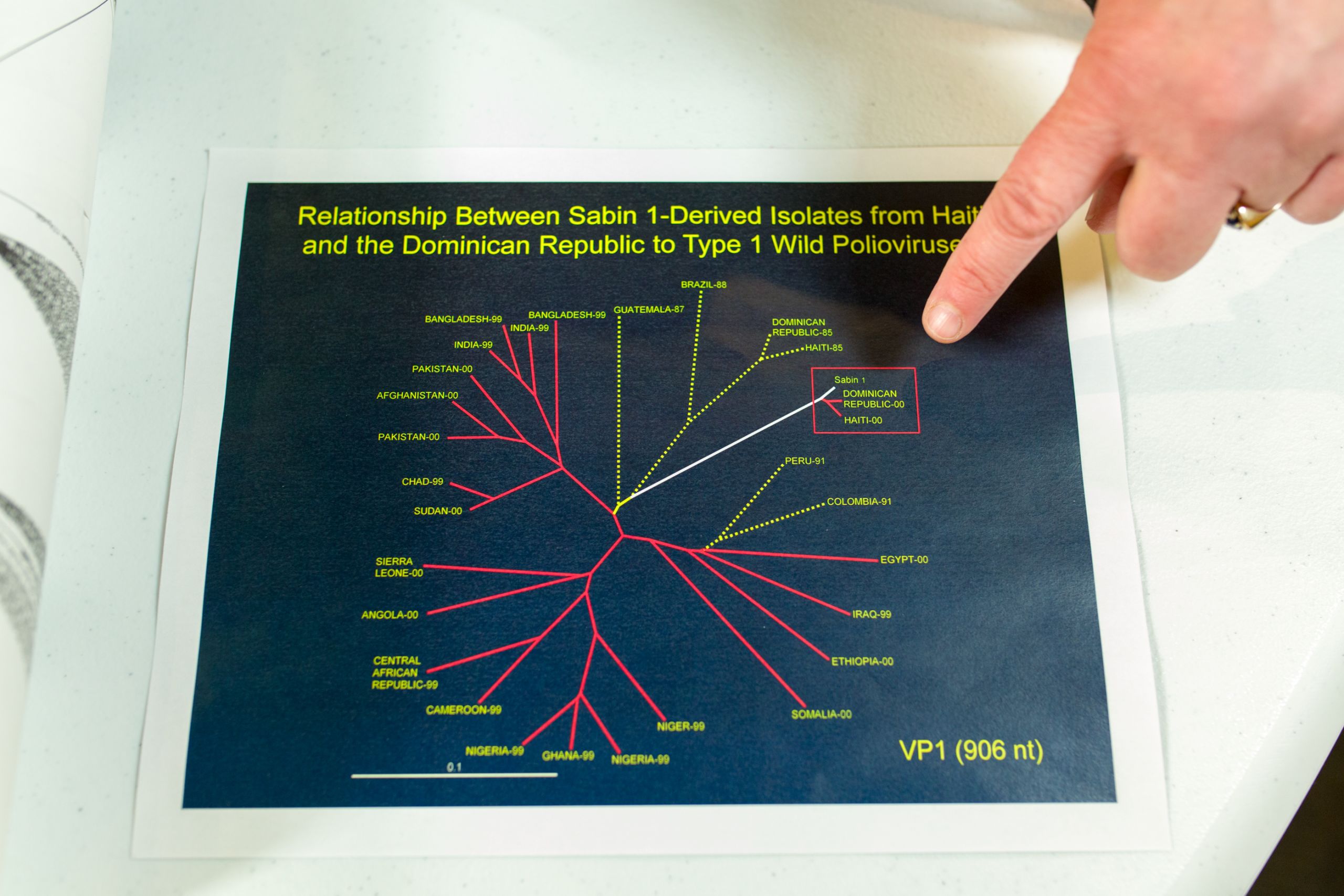

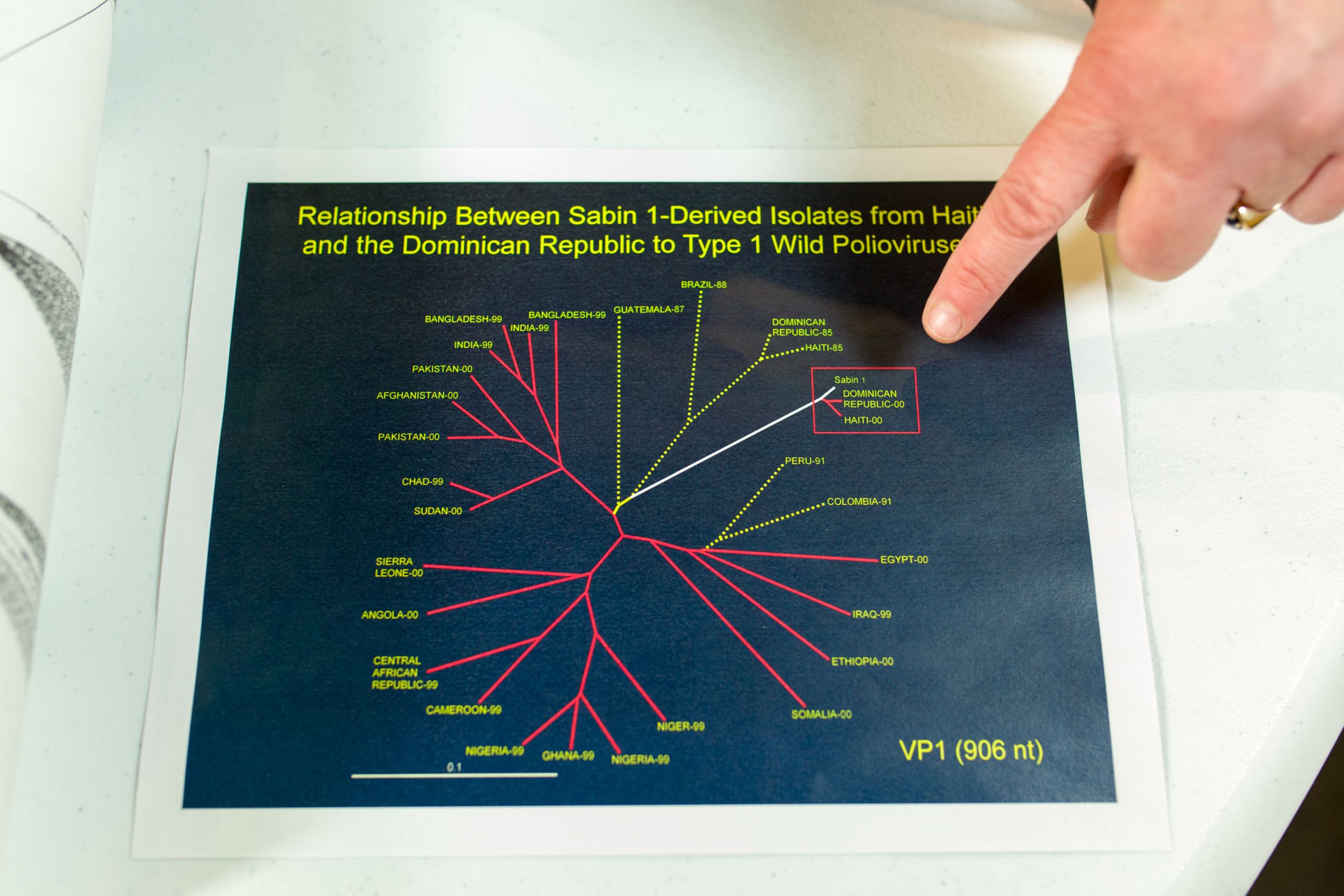

Burns and her colleagues worked to group “families” of poliovirus that had similar characteristics. They developed detailed dendrograms – like a family tree – that showed the relationships of viruses - the further from the main “trunk” – the greater and older the genetic drift. The sequencing could show when poliovirus families had been extinguished, and which ones were thriving, and possibly traveling to other countries.

A dendrogram, similar to a family tree, showing a surprising family of polioviruses that emerged on the island of Hispaniola in 2000.

A dendrogram, similar to a family tree, showing a surprising family of polioviruses that emerged on the island of Hispaniola in 2000.

In 2000, Burns and her colleagues were studying genetic sequences of poliovirus from the Caribbean and made a shocking discovery- an unusual cluster of viruses on the island of Hispaniola.

This new discovery showed that, very rarely, the weakened virus in oral polio vaccine could change over time into a form that caused polio disease.

Dr. Cara Burns describes the implications of the disovery.

Dr. Cara Burns describes the implications of the disovery.

CDC together with global specialized labs refined new methodologies and then helped to transfer them to other laboratories in the network.

“We came up with a definition of a certain amount of mutation that had gone on that typically was linked with a more dangerous virus," says Cara Burns. "We adapted the laboratory techniques so we could identify these outbreaks."

Currently about 100 laboratories in the network have the capacity to identify circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses.

This capacity continues to serve the polio eradication program well - allowing it to distinguish between wild poliovirus and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks. This in turn allows the program to tailor vaccine campaigns and other strategies to stop transmission of polio.

Global Coordination and Cooperation

The Global Polio Laboratory Network can not only identify changes in poliovirus, it also coordinates to understand how and where viruses are spreading. An enormous database of more than 10,000 virus sequences allows the laboratory network to rapidly compare viruses from different countries and regions.

In 2011, for example, there was a polio outbreak in China, a country which had last seen indigenous polio in 1994.

Dr. Burns describes how the laboratory network traced a 2011 outbreak in western China.

Dr. Burns describes how the laboratory network traced a 2011 outbreak in western China.

Cara Burns hopes to have a consolidated sequence database so that any future polioviruses can be rapidly compared to previous viruses – whether wild or cVDPV.

More than polio

Today the Global Polio Laboratory Network is not only working on polio, but 84% of the polio laboratories are also accredited to identify measles and rubella, and similar laboratory techniques can also be used for influenza.

Dr. Burns explains why the global polio laboratory network has been successful.

Dr. Burns explains why the global polio laboratory network has been successful.

“When we talk about issues such as global health security, having all of that breadth of the polio laboratory network is really important. Molecular sequencing is important, but having the capacity to isolate viruses in countries is really critical not only for polio, but for other diseases.”

Cara Burns at the CDC building in Atlanta.

Cara Burns at the CDC building in Atlanta.

Taking the Politics out of Polio

A Rotarian's work in Pakistan

Aziz Memon knows about the need to advocate at every level of government. The Rotary PolioPlus Chairman and industrialist devotes much of this time talking with the politicians of Pakistan about polio eradication.

Rotarian Aziz Memon talks with his team in Karachi, Pakistan.

Rotarian Aziz Memon talks with his team in Karachi, Pakistan.

“On a politician’s busy agenda, polio eradication can come if not last, then near to last,” he says, in an interview in his Karachi office. “One needs to remind them again and again that this task is not done until we reach zero polio, and even then we need to continue to be vigilant for years to be truly polio-free.”

I have just one agenda, that is to take care of the children and finish polio.’”

Watch the video below to see how Aziz Memon works to keep the politics out of polio, and continue scrolling to learn more.

Aziz Memon has taken risks to end polio in Pakistan. Watch to find out more.

Aziz Memon has taken risks to end polio in Pakistan. Watch to find out more.

The challenges to polio eradication in Pakistan have been many.

One was the devolution of powers, including health from the federal government to the provinces in 2011.

“It is just not only keeping the federal government engaged but it is having the provincial governments engaged – and they are run by different political parties,” explains Memon. “And the fact is, these political parties don’t get along with each other. But for polio we need to request that they sit on one table and talk about it.”

Rotarian Aziz Memon and members of his Rotary polio team in Karachi.

Rotarian Aziz Memon and members of his Rotary polio team in Karachi.

With elections on the horizon in 2018, Memon and his colleagues worked hard to have a declaration signed by all parties, promising to make polio eradication part of their election manifestoes. This took the politics out of polio.

Memon says he personally stays out of politics. He says it's important to stay neutral, allowing him to speak in good faith with anyone.

Memon presses on the big political issues, and smaller ones as well. For example, he describes the challenge of building managers forbidding polio vaccinators from entering their high-rise apartments, where dozens of young children who should be vaccinated might live.

The Karachi skyline.

The Karachi skyline.

“So we have to work our way around with them, ask the permission of the president or the secretary, and promise to be responsible for the activities of these vaccinators. We have been providing cards to the vaccinators so that they can show that they are not just trespassers, not just street criminals, they are bonafide vaccinators, and that’s helped a lot.”

Each of the lessons from polio have been hard-won in Pakistan.

Polio has been a thorny and, in some years, dangerous program.

It has withstood a murderous period when militants banned the program in some areas; dozens of vaccinators and several security officers killed; and community trust in polio vaccines plummeted. Rumours and mistrust grew after a CIA plan that involved a fake door-to-door vaccination campaign to locate Osama bin Laden.

In Waziristan, one Taliban leader banned polio vaccination campaigns and said he would restart them again only when drone attacks were stopped.

Memon tried various routes to reach him to change his mind, but finally had to travel to meet him one-on-one.

“I had to go there alone without my cell phone so it was scary, frightening,” he remembers. “I told them ‘I can’t stop the drone attacks. You must be joking.’ I gave them the message that these children could be your own children."

In Pakistan’s difficult recent history, this was one of many encounters.

“There were several other instances like that where we had to convey to various leaders that they were being misled, and that they were misleading the people and creating a generation of crippled children.”

Memon is relieved that today, those dangerous periods are mostly behind the program. In 2018, Pakistan is recording the fewest polio cases in its history. Continued political commitment and quality campaigns could soon end polio transmission in the country.

If there are problems, Memon will be there to help solve them. He looks forward to the day when polio is finished, and to the legacy that will leave his country.

“I think that for Pakistan the biggest message and victory in eradication of polio means that we have the capacity to improve routine immunization, we have the capacity to stop other vaccine-preventable diseases.

"Ending polio proves that we can do even more for children’s health.”

Acknowledgements

Our World United to End Polio is the result of a collaboration of the United Nations Foundation, with partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Christine McNab, an independent multimedia producer specialising in global health and development, produced the series. The project was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

OVERALL PRODUCTION

Executive producer, photographer, writer, narrator: Christine McNab

Video editing: Kathryn Dickson, OnFireFilms.tv

Graphic design and animation: Ron Sloan

Music, Re-recording Mixer: Michelle Irving, Soleil Sound

Colour correction: Mario Baptista

Cameraman Rahul Negi.

Cameraman Rahul Negi.

Ending Polio in India

Camera and sound: Rahul Negi

With special thanks to:

Dr Pradeep Haldar, Deputy Commissioner for Immunization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India

Dr. Sunil Bahl, Regional Advisor, WHO South-East Asia Region

Dr. Pauline Harvey, Team Leader, NPSP, WHO Country Office

Dr. Pankaj Bhatnagar – DeputyTeam Leader, NPSP

Dr. Vishesh Kumar – NPSP Regional Team Leader for Bihar

Dr. Rajendra Kumar Singh, SMO, NPSP Darbhanga

Martha Dodray – government healthworker, Darbhanga

Gladys Lingat and the team at the Mabalacat City Health Centre

Gladys Lingat and the team at the Mabalacat City Health Centre

Empowering Countries

Camera and sound: Derek Bauer, db Productions

Additional photographs from the CDC Public Health Information Library

With special thanks to: Dr. Cara Burns, Dr. Mark Pallansch, Dr. Olen Kew , Allison Maiuri and Holly Patrick at the US Centers for Disease Control

Haider Ali and Qaiser Shahzad

Haider Ali and Qaiser Shahzad

Taking the Politics out of Polio in Pakistan

Camera and Sound: Haider Ali

With special thanks to:

Many at Rotary PolioPlus in Karachi, Pakistan including

Mr. Aziz Memon, Rotary PolioPlus Chairman

Ms Alina Visram, Rotary PolioPlus, Pakistan

Mr. Qaiser Shahzad and the teams of supervisors and vaccinators we spent time with in Karachi.